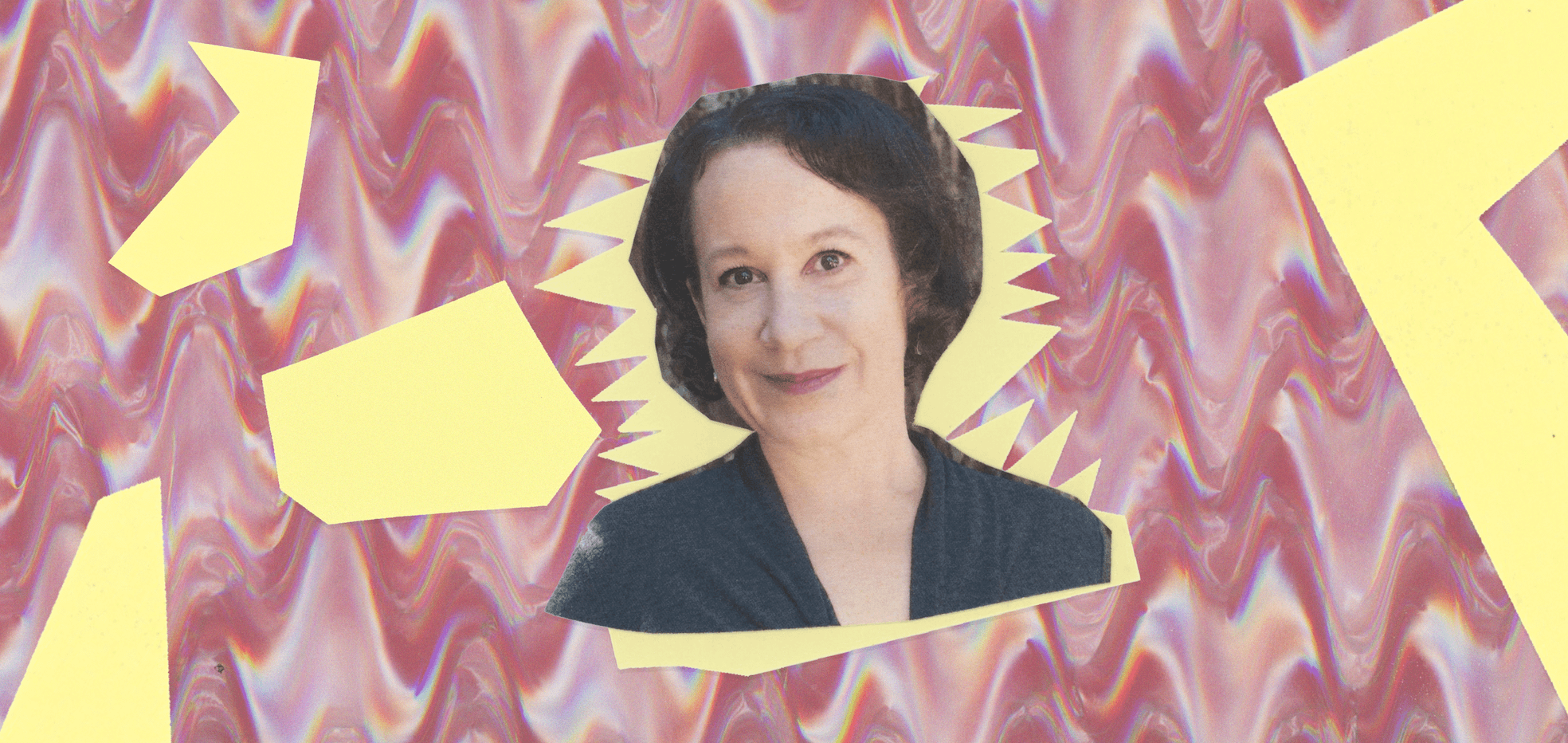

As an engineer, UX designer, product manager and startup advisor for more than 20 years, Laura been part of every type of team – from those that have to deliver on the sometimes unrealistic expectations of upper-management to the ones that suffer from too many opinions on the ground floor. Now the Vice President of Product at Business Talent Group, she has honed her expertise into a set of best practices and published them in two books: UX for Lean Startups and Build Better Products.

I hosted Laura on our podcast to learn everything from why assembling a great product team is like pulling off a heist, to tips for improving collaboration and marrying business needs with user goals. If you enjoy the conversation check out more episodes of our podcast. You can subscribe on iTunes, stream on Spotify or grab the RSS feed in your player of choice.

What follows is an edited transcript of our conversation.

Adam Risman: Laura, welcome to Inside Intercom. Can you give us the CliffsNotes of your career to date and what you’re doing today?

Laura Klein: Since the mid ’90s, I’ve done research, I’ve been an engineer, I’ve done user experience design, and now I do product management. I am the Vice President of Product at Business Talent Group, where we help find really good freelance jobs for high-end consultants at very large companies. My whole job is to help take a fairly analog company and make them a little bit more digital. I’m currently building a lot of internal tools to help folks do their jobs more efficiently—and to help them scale.

Adam: You’ve also managed to write two books. I imagine when you’re working with companies like those that you’ve consulted with over the years, you end up repeating many ideas over and over. That must give you a good idea of what you want to put on paper.

Laura: Exactly. When I wrote Build Better Products in 2016, it honestly came out of a ton of consulting. I was working with a bunch of different companies and teams of all different sizes. I was often asked the same questions, and I found myself leading these workshops many times. I’d go up to the whiteboard and start to draw something. If I don’t grab a Sharpie and start writing on sticky notes or start writing on a white board –hopefully not with the Sharpie – I’d lose my ability to call myself a UX designer. So I’d start drawing these diagrams of our user map, or our funnel, or whatever it was. After a few, I found I was drawing the same thing over, and over, and over. I started developing these exercises, and reproducing them in workshops. A lot of the book is made up of activities that came out of just being in rooms with teams that all had very similar problems.

Balancing business goals with user needs

Adam: What are a few of the most common problems you kept running into?

Laura: Metrics one of thing people often ask about. Everyone wants to know which metrics they should actually care about. You ask them: “What does the funnel look like for this particular feature? What’s the behavior you’re trying to create? What are the steps people are going to go through? How do we measure to make sure that people are doing the things we want them to do in the way we way we want them to do it — and that they’re happy?”

One exercise I use all the time – and it’s so easy for folks to do – is called “backing out.” Let’s say your CEO comes to you and says: “We need to build this feature. It’s going to be great.” There’s this really hard conversation you have to have if you’re a product manager, where you need to say,“No!”. You have to ask: “What are you hoping to get out of this feature from a business perspective? How do you see this helping our users reach their goals in a way that is helpful to them and helpful to us?”

Hopefully you can get them to the point where they say, “This is going to increase retention for this particular segment of users.” Then you can sit down and generate a bunch of other feature ideas that could potentially do the same thing. Suddenly we have an array of options we can take to engineering and figure out which one most effectively delivers the result we want. Alternatively, maybe retention among a certain group of users is already at 112%, so it’s a great feature idea but maybe it’s not our top priority right this second. This helps you move the conversation into a place where you can discuss the merits of a feature in a more objective way. I have a lot of prioritization activities like that one.

Adam: It sounds like it all comes back to setting the right business goals early on and making sure that everyone is aligned. Do a lot of companies and designers overlook that part?

We all should understand and care about both the business and the users.

Laura: Sometimes companies can be very idea-focused. They’re not coming at it from the perspective of solving a user’s problem; they want to build a cool thing, and then they’re shocked when nobody wants to use it.

In some organizations there’s a troubling split: the product manager is in charge of the business but the UX person is the defender of the user. And they have to battle it out in the octagon. I don’t like that approach at all. We all should understand and care about both the business and the users. I never want UX designers to care so much about the business that they use dark patterns or they trick users. That’s not okay. But I also don’t want product managers to have an adversarial relationship with upper management’s business goals. I want to be given a goal to hit, and then I want to be given the freedom to work with the rest of my time to figure out the best way to hit that goal by understanding the users’ needs, what their current behaviors are and how we might change those behaviors. I do get frustrated with designers and researchers who think, “I don’t need to care about the business. I’m a defender of the user.” That’s great, but you’re being paid by the business so let’s maybe make good decisions for all of us.

Adam: What’s your advice on finding the balance between the needs of the user and the needs of the business? Because sometimes putting the business first can be rewarded internally. Do you need to choose?

Laura: I don’t think you do. I think we should always be looking for win-win scenarios first. Every so often, you’re going to have to go one way or the other, but when we find that the business and the user are in conflict – or we’re thinking from the perspective that if it’s a good business decision then it’s going to be bad for the user – that’s just a bad place to be. Maybe that means that your business model is screwed up. If you’re not actually offering value to your end use, then that’s a problem in itself.

I believe making things better for the end user should always turn into a good business decision at some point. You do occasionally obviously have some trade-offs. For example as a product manager, I like to always pay down tech debt as we go. I don’t like to build up a ton of it. I like to include time in every sprint to take care of things like bugs, upgrades, etc. But it can be hard to justify that in terms of the actual end benefit to the user. I will say this: sometimes you do have to pick between users. That is a big, hard choice to make because not everything you do will help every single user of your products.

What collaboration is and isn’t

Adam: You mentioned all these different points of view in a product team: research, design, engineering, product management – and everyone’s trying to empathize with one another and meet in the middle. When you parachute into a businesses, how do you sort of take stock of the team dynamics and build rapport there?

Laura: I like to talk to everybody on the team and understand their points of view and what they’re struggling with, because you don’t ever want to assume anything about the way things work. I’ve worked with a lot of engineering teams, and they’re just like us: they’re humans, and they all want to work in different ways. Some are excited to be involved in certain kinds of decisions, and others really don’t want to hear about it. You need to figure out how to all have shared goals on the team, while still respecting people’s desire to operate in the way they feel they works best.

The right people need to be making the right calls. Everybody should have as much input as they want to have, but the decisions are actually getting made by the right people. That’s often very difficult in large organizations, because there can be a whole bunch of layers of management above you who swoop in and say: “Nope. You’re going to do it this other way.” But in the ideal world I’m trying to create, where we have somewhat autonomous teams, you want upper management saying: “These are your goals. Go hit them.” Then we all work together to figure out the right way to hit those goals.

Talk to everybody on the team and understand their points of view.

I’m a huge fan of cross-functional teams. I’m a huge fan of being collaborative. I worked in the days of waterfall, and I get throwing the 400-page deck over the wall to the engineers. I’ll tell you: I know all the reasons it doesn’t work, and I don’t want to go back to that. I’ve also seen teams go the other way, where they feel like collaborative means that every single person on the team does every single thing together. That’s a nightmare, too. We don’t all have to be in a six-hour meeting, trying to get 15 people to collaboratively design a comments section. That’s not what collaborative means.

There are people who are specialists in certain areas, and they should be in charge of getting feedback and input from the correct people, and they should also be in charge of making the calls on certain things. I also don’t think that person who’s making every single call always has to be the product manager.

Adam: How do you feel about the DACI model? Is that something that you think is beneficial, or does it need to be that rigid?

Laura: If it works for your team, I think it’s great. I haven’t done anything that rigid, where it’s so specific. I tend to work on smaller teams, and we just figure it out. I’m a big fan of figuring out what people are good at and giving them responsibility and authority in those areas. I like bringing people up who may be more junior and giving them smaller decisions that they get to make.

When it comes down to it, every single person on that team is making a million decisions a week at the micro level. Scaling that up a little bit and giving people a little bit of rope is a good thing, generally speaking. But it’s hard, and it does make it much harder than if I just got to dictate everything that’s happening. You’re giving a lot of people a lot of power to ship something. That’s why it’s so important to make sure that people have the information they need to make good decisions, and that they know what the actual goal is. Their view of the world can’t just be the next ticket.

Heist-style collaboration

Adam: You’ve compared a well functioning product team assembling an “Ocean’s 11”-style heist team. Can you expand upon that?

Laura: I just love heist movies. I also considered going with a basketball team, because I’m also a huge basketball fan, but I went with the heist metaphor because I didn’t want to jinx my team. I was going to be giving this talk right in the middle of the NBA finals.

Think about your favorite heist team: You have the leader who’s getting the gang back together for the one last job, after which they’re all going to retire to the beach. They always put together a team of specialists and experts, and it’s a team that is comfortable working together often, sometimes after some fighting. But usually by the time they’re ready for the heist, there’s a lot of trust there.

The reason there’s trust there is because everybody knows their stuff. The leader doesn’t necessarily know how to crack a safe, or how to break into the alarm system, or how to drive a getaway car. But what the leader does know is how to pick the goal and the target. The leader knows all of the “why” – why it’s the right target right now, what it’s going to take to happen, and what the deadline is. Then everyone goes off and does their own stuff, but there’s a lot of collaboration there, too. The safe cracker has to be talking to the explosives expert, because maybe the safe cracker needs some explosives to get into the safe. They’re all working together, but when it comes down to who’s going to crack the safe, we’re not all doing it together. There’s one person there in charge.

It’s not a perfect analogy, but whenever I’m looking for a team I would actually want join, it tends to be a team of people who are really good at the things they do, and they have a lot of respect for the things the other people do. They can give input, but they know that’s where it ends. For example, I can give input on the data base schema if I want to, or if I have a strong opinion, but the CTO or the tech lead makes that final call.

Making remote product teams succeed

Adam: When it comes to this type of cross-functional collaboration, how is that complicated by the rise of remote teams? Can a remote product team succeed in this way, and if so, what do they need to do?

All-remote teams work better than partially remote teams.

Laura: I’m glad you asked, because my CTO currently lives in Hawaii. Some of my engineers are in Panama. I have a project manager in San Francisco. I’m in Silicon Valley. I’ve had a visual designer check in with me from Myanmar, where she was traveling. So, I have a bunch of stakeholders in various parts of the country, and occasionally parts of the world.

I think all-remote teams work better than partially remote teams. For example, having a bunch of decision makers in a room together and having one or two remote people can be really difficult, because those one or two people can be left out of discussions. Having more people remote – and behaving as if everybody is remote – is the best way to go if you’re going to have some people remote. The thing that worries me the most about remote teams is getting three or four people into a room, and they start making decisions and moving on without the rest of the team. Then the rest of the team gets left behind because they weren’t there for that conversation.

There are a lot of tools now that make it easier to share information, but I’m going to be honest: it can be harder. I’ve done this where we’re all literally sitting in the same office, and I’ve done this where we’re sitting all over the world. All-remote has its own challenges. My whole company is spread out, and it’s harder to know what’s going on, it’s harder to get involved, and harder to remember that you’re supposed to loop in somebody from customer service or legal. Although, I never forget to loop in legal, because they will remind me. That said, I think lots of companies are doing that now because we have to.

Adam: So, whether I’m in Myanmar and you’re in the Bay – or you and I are sitting across the table along with our whole engineering team – what are some quick tips our listeners can take home with them to improve their teams’ collaboration?

Laura: One fun thing is for designers to ask engineers who they think the user is and describe the user of a particular feature. I use an exercise in the book called “the user map,” where I have 16 questions teams should answer about their end user.

Nobody ever has the answer to all 16 by the way; I always feel like I’m setting people up to fail a little bit on that one. I’d rather certain people not have some of the answers than for all the people have different ones, if that makes sense. For example, there’s the question of, “How does this feature improve users’ lives?” I’d rather have somebody just leave that blank and say, “I don’t know,” rather than have everybody come back with a totally different answer. The first one’s really easy to fix; the second one is much, much harder.

This is a lightweight persona, where you just ask people: “Who is our user? What do they do? What are they trying to do? What are their goals? What are their behaviors? How are they using our product?” The goal is to understand what everybody’s baseline understanding is. Then, there are a bunch of activities that you can do together to help decide things. For a particular feature, you ask: “Who are we building this for, and what do we hope to get?” And then it’s about making sure everybody is on board. It’s not just that this is the ticket you’re going to fill, or this is the onboarding flow you’re going design, or this is the feature you need to write a spec for; it’s that you’re trying to hit a goal for a specific type of user and you understand why. Everyone should have the same answer to that question. Coming back to the heist: this is the bank we’re going to hit, and this is why Thursday at 3 o’clock is the right time to do it.

Adam: Thanks so much for joining us, Laura. Where can our listeners go to keep up with what’s new with you?

Laura: There is the very rarely updated, usersknow.com. You can find my books there, as well as my podcasts, which will start again later this summer.