As the CEO of ProfitWell an expert in pricing for the better part of the past decade, Patrick receives an endless stream of questions from business owners who want to know how much they should charge for their SaaS products. The problem with silver bullets? They don’t exist.

Landing on the right price depends on a complex blend of factors. But as Patrick has discovered, developing an intimate knowledge of your customer personas may be the single most important step you can take – and that includes knowing what kind of customers you don’t want to target.

Patrick joined me at the SaaStock conference in Dublin to record a live podcast, where we talked about everything from how to raise your prices gracefully to the pros and cons of freemium products. Short on time? Here are five quick takeaways:

- Your price is the exchange rate on the value you’re providing. In addition to a solid understanding of who your customers are – and aren’t – Patrick recommends taking a deep look at value metrics like pricing based on people as well as features.

- Freemium is an acquisition model , not a revenue model. You should only have a freemium plan when you understand your customer well enough that you can convert them from free to paid users. Free product can’t be bad; it absolutely has to be as good as a paid product.

- Don’t be afraid of raising your prices, and don’t “grandfather” existing users. Focus instead on making it an easy transition and clearly explaining the added value that has led to the increase. Do, however, have a contingency plan for customers whose core business may be torpedoed by a price hike.

- If you’re in a financial position to bootstrap your company, like ProfitWell has done, go for it. But remain open to the possibility of taking on funding, too. If your growth vectors require it, avoiding a cash injection could actually be negligent to the company and its stakeholders.

- Content is a crowded marketplace, and even tougher to stand out now that major new channels are no longer launching every year. Quality remains the only way to rise to the top, and for Patrick it comes down to the three approaches: create a good experience, treat people like people and don’t be so pushy.

If you enjoy our conversation, check out more episodes of our podcast. You can subscribe on iTunes, stream on Spotify or grab the RSS feed in your player of choice. What follows is a lightly edited transcript of the episode.

Geoffrey: Patrick, welcome to Inside Intercom. Could you take us through your career trajectory to date and how you ended up running ProfitWell?

Patrick: I’m from a small town in the middle of Wisconsin; I grew up on a farm with more cows than people, essentially. That shapes a lot, so I like to throw that in there. I basically wanted to be a doctor then wanting to be a lawyer, which is kind of the standard lower-middle-class trajectory. If your family members are laborers, you want to go into kind of the next “rung”. But I ended up going to school for economics and rhetoric, which was kind of a weird combination, mainly because I went there on a debate scholarship. And so it was one of those things where it was relatively easy and I could learn a lot about math and statistics.

Out of school, I worked for the US intelligence community. That was really interesting, because it was post-911, pre-Snowden. That’s where I learned a lot about economic modeling in a very practical case because when you’re hunting a bad guy or gal, and when it comes to intelligence, there are a lot of different things you have to understand, and you have to work through the problem. I didn’t really like working for the US government. It’s very, very bureaucratic as most governments are. It wasn’t that I didn’t feel the mission; it would take a long time to get things done, and the learning curve slowed down.

I went and worked at Google, and that’s where I came to Boston from DC. At Google, I was working on sales operations and doing very similar things, but instead of hunting bad guys or gals, I was hunting money. It was a very interesting, again, to make practical applications of things.

Geoffrey: I’m sensing a theme.

Patrick: Yeah, it’s a little bit of a theme. I come from that blue-collar background and a no-BS union dad if that makes sense, and he’s also in the military, so it was like a very low penchant for BS. I ended up wanting to leave because I had worked on a project that made Google quite a lot of money, but it was one of those things where, because of Google’s size, other projects were prioritized because they made more money. It wasn’t that I didn’t get any cash, I, is basically, hey, that’s not a good priority if this other project is going to make more money. It wasn’t that I didn’t get any cash – I got this award and stuff like that. It was more that they were going to shut the project down, and I felt I just wasn’t learning enough.

I worked at a customizable jewelry startup in Boston, kind of like Blue Nile where you can kind of pick your gemstone, pick the ring, et cetera. That’s the first time I started working on pricing and started really on a micro level applying value models to try to determine value within a business. Again, I didn’t really love the culture, so I thought that in a worst-case scenario I could go get a job, be a barista, dig ditches or whatever.

So I jumped out and cashed in my very small 401k retirement fund, had about nine months of runway in Boston and took a risk and started ProfitWell. It’s been about six years. We’re fully bootstrapped, and we’ve grown to about 60 people. I finally pay myself a little bit of money so I can kind of survive. That’s the trajectory so far.

“A debate scholarship was one of the best things to happen in my career”

Geoffrey: You mentioned a debate scholarship. I believe you’re a national debate champion as well, is that correct?

Patrick: Yeah, I am a national oratory champion. It’s a little bit different than debate you may have seen on TV; it’s called individual events. It’s interesting because you’re an individual competitor, but you’re also on a team. I went to a school that consistently ranks in the top three in national tournaments. You can actually get into national finals and multiple events. In my career, I’ve had 13 national finals (and then the one title that I won). We also won the team title my senior year as well in oratory, which is kind of like a platform, 10-minute speech that you prepare. It was actually on the education system in the United States.

Geoffrey: Do you think that that has helped you in the world of business?

Patrick: That and working at the NSA have probably been the most bedrock things. The reason for that is because there’s this event called “extemp” that I turned out to be fairly good at. Extemp is when you go to the round, you draw three questions, and they’re all geopolitical. For my last national final, I believe the question was “How will the Russian-Venezuelan oil deal affect US relations with Belarus?”

You get a question like that, and you’re like, “What?” You have 30 minutes to prepare and you’ve filed, you’ve done a lot of research. We have these tubs of files that are basically just news sources from every single news source you can think of, from The Economist to the Agence France-Presse to the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. You prepare a seven-minute speech, and in a national final you probably need 14 sources. You have to memorize all this and create the argument in 30 minutes and give it flawlessly in front of room full of hundreds of people at that level.

It’s like a pressure cooker. Structuring an argument, thinking through a problem and helping communicate that particular problem and finding the truth in it – I think those are the biggest things, and I couldn’t have asked for a better training. It wasn’t something that I thought I was going to go into, and it was an event that I didn’t really respect. So it was one of those things where it became one of the best things to happen in my career.

There’s no silver bullet for pricing

Geoffrey: You’re maybe best known as probably the expert in pricing, certainly in B2B SaaS. What sort of advice do vendors come looking for you as it pertains to pricing?

Patrick: We’ve thought about pricing in the world of subscriptions probably a lot more than most people. I think there’s a lot I’m still trying to figure out. For example, Intercom is one of the best companies in the world in product. People ask you, “How do you do good product?” Well, there are a lot of factors that make you good at product, and there are a lot of things you have to do.

With pricing, a lot of people want a silver bullet, and they don’t realize that your price is the exchange rate on the value that you’re providing. When you look at pricing in that context, all of a sudden there are a lot of different pieces you have to think about, but there’s also a little bit of comfort because it’s a centralized problem.

The top two things I recommend are to really understand who your personas are – whom you’re actually trying to sell to – and then the jobs to be done, which I know Intercom is a big proponent of. When you do those two things in context, it starts to center what your pricing strategy should look like, which really is less about what you should do and more about what you shouldn’t do and whom should you not target, whom should you not go after, whom should you not price for.

Then the more tactical piece is pricing around value metrics. At Intercom, you price based on people as well as features. That people aspect is super important, because if you get everything else wrong but you get that value metric right, it’ll be different to other types of businesses. That typically will carry most of your pricing forward. There’s no silver bullet to the process, unfortunately. I wish there were a silver bullet – I’ve been trying to find one so I can sell it – but it’s not that simple, not that straightforward.

“Price is the exchange rate on the value that you’re providing.”

Geoffrey: You’re probably talking to a lot of early-stage startups here at SaaStock. A common drop a lot of early stage startups are falling into is pricing too low. When someone comes to you about low pricing, what’s the advice you give them?

Patrick: Historically, European companies (especially in the world of SaaS and subscriptions) do price their products too low. I think there’s a bit of a psychological phenomenon, especially in the Eastern Block and the Nordics, because during the Soviet era you didn’t get access to new technology, and so it became about being really good in engineering and really good at efficiency. I would argue that Europe really devalued its work. In the US, on the flip side, normally the prices are a bit too high. There’s probably a whole arrogant American tangent that we could go on.

When you’re pricing too low, you have a phenomenon where the people who are willing to pay that price (often they’re willing to pay much more), and then there’s a good crop of people who actually don’t trust that you’re able to do what you say you can do. If Intercom said, “We’re going to give this to you for 100,000 people for $10 per month,” there’s clearly something wrong. I’m worried the product isn’t great or that it’s going to be a waste of my time, especially if I’m a legitimate customer who has the potential for 100,000 people.

My recommendation is just to do some research. That’s really what the crux of pricing is: doing some sort of customer development around asking customers or target customers in the right manner about where their willingness to pay is and asking them a range of questions. What you can then do is just level set and be very dispassionate about determining what the price should be or identifying that the price should be here, but the customer is way over there. At that point, you have to pick a customer instead of averaging it out, because you can’t be everything to all people.

The future is freemium

Geoffrey: You’ve also written a lot about the topic of freemium as well, and you’ve described it as sneaking leads into your funnel. Could you maybe tease that out and talk us through the pros and the cons of freemium?

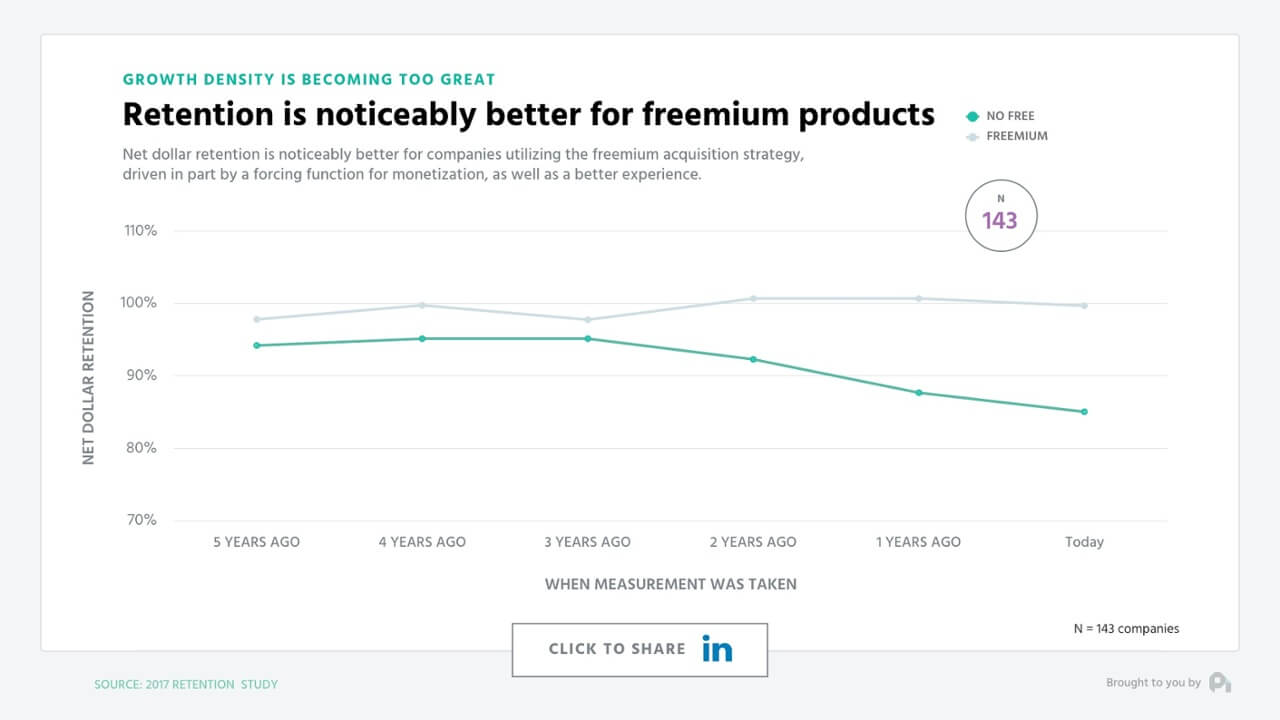

Patrick: I think freemium is absolutely the future for most companies. What we’ve noticed in the market – and we have actually the data for this – is that the proliferation of technology has made building a company relatively easy. Not building a great company, not building a good product, but building just a company by spinning up a server and a website. What’s happened is you have just rampant competition. More and more people are flooding marketing channels. We’re not getting new marketing channels every single year or every single quarter like we once were, so there’s all this density happening.

The answer to density was going from PPC to content. But now content is getting dense. There are a lot of people who are good at very good content. You can try to make excellent content, but it’s a logarithmic curve from “very good” to “excellent”, right? It’s not something where it’s just linear, we’ll just put in some more work. It’s a lot more work. You think about that, and the question becomes, “How can I get good leads?” Now it’s going to become about building product. If I can actually give you some value with a product, then all of a sudden I might be able to get those leads, and then the unit economics work out.

We’ve seen this in the data around CAC as well as in the data around NPS scores. People who come into a product based off a freemium plan have noticeably higher NPS scores than the people who convert just from a sales conversation. The reason for this is that freemium is an acquisition model, not a revenue model. You should only really have a freemium plan when you’re probably three to four years into a business, and you understand your customer enough that you can understand how you can convert them from free to paid.

I think the pros are starting to become very obvious. The cons are that a free product can’t be bad. It has to be good. It has to be as good as a paid product. We have a free product that rivals the paid products that are in the market, and we spend an exorbitant amount of engineering and product resources on continuing to develop that product. Depending on your funding situation, freemium can be very expensive. We had to basically stop some of our development or our trajectory because we knew this was the future, so we had to slow down in some areas to speed up in this area. There’s plenty I can get further into, but that’s the big crux I would argue with freemium.

Geoffrey: You mentioned that you see a lot of companies moving from marketing-qualified leads and sales-qualified leads to product-qualified leads. If you’ve got someone on a free trial and they’re showing some kind of intent, it can actually result in customers who were exponentially more valuable to your business, right?

Patrick: Yeah. The whole inbound marketing movement was basically a huge shift toward not being pushy and letting people start coming to us. With freemium and just the ability to start creating better and better product (which is extremely difficult), it’s no longer about the technical aspects. We’ve figured a lot of those out. There are always going to be big problems, especially when you scale. But it’s not like we’re worrying about keeping the physical servers up and running. That’s not an issue for us anymore.

Because of that shift in the market, we’re now moving to a place where I’m going to go even further away from you as a lead. I’m going to wait for you to come to me, I’m going to nurture you in some particular manner, and I’m not going to try to be pushy, because as long as you know I exist, when you have the need, I want to be the first person you come to for that need.

“You have to think about monetization as more than just the price.”

How to raise your prices

Geoffrey: What sort of advice do you give to customers who are thinking about raising their prices? Are there any examples that have gone particularly well or particularly badly?

Patrick: I think the first thing to get your mind around is you shouldn’t “grandfather” your existing customers. That’s not a common term in Europe. A lot of people think their existing customers should keep the same price for the life of them being a customer. It feels really good. The problem is, is that when you go from zero to 10 million, it works because you’re hitting on those first layers and those first channels of growth. Once you get over 10 million, just from an analytical perspective, it’s extremely difficult to go from 10 million to 100 million without raising prices on your customers in some way. For a lot of us, we have constraints where it’s going to be hard to build another product we can sell to them, because there’s a little bit of survivor bias. There are a lot of problems with getting one product right, let alone two or three. We have to improve our current product and then raise the price for those customers.

What you can do is make this an easy transition. That means if you have support problems or NPS issues, you shouldn’t be raising your prices. You need to go solve those product problems first. Assuming those are okay and you’ve added value, customers of B2C and B2B realize that things cost money. Again, the price is the exchange rate on that value that you’re providing. Because of that, you can push forward and be very direct with them by saying: “Listen, we’ve provided a ton of value. This is great for you. It’s great for us. For us to continue providing you more value, we do need to raise our prices. Here’s what the prices are.”

You can soften this language with a lot of things. The first thing is you can provide a grandfather discount: “You’ve been a loyal customer. Thank you so much. We’re going to give you the next year for the current price, and then after a year this discount will fall off.” One really nice thing I like to use that I picked up from Expensify is using the PS line of the email to say, “If this materially impacts your business, please reach out and we’ll work something out.” You want a little bit of a relief valve. There are some people for whom a price jump might be disastrous, especially in B2B software.

You also want people who are kind of in the middle – let’s call them troublemakers put it nicely. You want them rethink being buttheads, if that makes sense. Maybe they understand they’re getting much more value, but they always want the lowest price. I’m kind of that customer, myself. Often times, you will want some sort of a salvage offer that your customer success team can give them to basically satiate their feelings.

I think the biggest thing is you’ve just got to make some movement. Deadlines are probably the biggest tactic here. Your pricing change doesn’t always have to be raising the price. It can be moving a feature, reducing your value metric or a whole host of different things. Start small and just get some momentum in getting comfortable doing it.

Geoffrey: How do you optimize pricing on an ongoing basis without causing potential damage?

Patrick: It should be as easy as testing your landing page. The problem is a lot of technology and infrastructure have held us back. Just think of billing systems, right? Stripe has made it relatively easy, but you also need an engineer typically to build a new plan, or to build some sort of back end that allows someone to create a plan. With most of the other subscription management systems, it’s easier (but still not incredibly easy) to manage all of those plans. Some of them are working on this problem. You have to think about monetization as more than just the price, because what you’re effectively trying to do is increase your RPU.

Raising your price is only one way to do that. Other ways to do that include finding better proportions of customers. If you observe that your Facebook leads always choose a low-end plan, while SEO leads choose the high-end plan, figure out how to optimize your SEO. It gets into product roadmapping and thinking about the things that are going to optimize these upgrade paths.

Add-on strategies are probably one of the least-used tools but have a high impact without being incredibly difficult to figure out. I guarantee you in most B2B software products, 20% to 30% of your base is willing to pay for priority support. There are all these different vectors that come with working on a price to increase that particular RPU, and that even gets into expansion revenue and things like that. There are a lot of things that you can dig into.

One really quick tactic, especially for European companies and even US companies who are selling into Europe, is if you have more than 15% of your base outside of your home region, you should be doing price localization. That means that cosmetically your price shows up as the currency of that person where they’re buying. But you’re also capturing the demand differently. If someone willing to pay for Intercom in the United States, the willingness to pay is going to be very different than someone in Dublin because the cost of living is different, the penetration is different and all these types of things in terms of the market are very different. Ultimately, it’s just going back to think through the problem and understand which vectors you can play with.

The pros and cons of bootstrapping

Geoffrey: ProfitWell is a fully bootstrapped business, something I know you’re very proud of. I’m sure you’ve had plenty of offers over the years, but talk us through the rationale behind staying fully bootstrapped.

Patrick: Totally. I don’t know if we’re particularly proud of it; we kind of get grouped in with the chip-on-their-shoulders bootstrappers, if that makes sense. We do like being bootstrapped. I think we were very fortunate with our ACV and our target customer, and we had the luxury of being able to bootstrap. But it has its cost to it, particularly because there are certain areas of growth that might have taken timeline off of our development that we didn’t have the cash to accelerate.

We probably will raise money at some point. If we don’t have to, of course we shouldn’t. But if we are looking at something where we understand our numbers, we understand the vectors for our own growth and we don’t raise money, it might actually be negligent to the company and to our stakeholders, which are the people who work there.

At the end of most of funding versus no-funding debates, funding is a tool, so let’s just skip to the end. At Intercom, you guys raised a bunch of money because it was a tool to accelerate growth. That doesn’t mean you’re bad at product so you hired salespeople, it just means that you deployed that capital really efficiently, but probably less efficiently than you wanted, because that’s just kind of what happens. Not having cash has forced us to be extremely efficient, probably to a fault. Our LTV to CACs are very high, and at first we thought it was really great, and then we were like, “Wait a minute, that means we’re not spending enough money to grow, right?”

We’ve run it really lean. I also think we were in a world where speed didn’t help us, mainly because the market is very weird. We serve subscriptions in SaaS. From a logo perspective, that market isn’t growing exponentially, which means we might have 60,000 target leads, and maybe half of those are Johnny and Jane startups or small companies. Then in the other half, there’s probably a good group of those that are mega-enterprise, which we’re not really going after. All of a sudden, we don’t have a huge market, so we have to think very diligently about how we’re going to go after that market.

Long story short, I think funding a tool. We’ll probably use it at some point. Right now, we like our optionality, and we don’t want to use it until we know what we’re going to do with it.

“If you want to be a billion-dollar company, it’s going to be very hard not to raise money.”

Geoffrey: We’ve seen companies like Buffer and Wistia – who are traditional VC-funded companies –buying out their original investors. Do you think that’s a trend that we’re maybe going to see more of?

Patrick: I think we’re going to see more of it. I’m really good friends with the Wistia guys, so I’ve got to make sure I don’t piss Chris and Brendan off here, but if we wanted to build Wistia today – yes, there are a lot of scaling things that would be very difficult – but the technology isn’t nuclear fusion. If you think about building a CRM 10 years ago, it was like building a nuclear fusion reactor. I know that sounds ridiculous, but it was, right? We really kind of, we kind of take for granted the cloud, dev ops, all of these different things.

If we want to build a CRM today, we don’t need to raise money. We already know what 18 months of our roadmap looks like, and maybe we do need to raise money because we’re not going to be able to go to market without that 18 months of roadmap, but we don’t need to raise crazy rounds. Right now, the market is insane. The rounds we’re seeing and the valuations that people are getting are very, very high. I think that we’ll see the trend more and more. It’s going to affect companies that aren’t trying to go for the moon, if that makes sense. I think Wistia wants to grow aggressively, but they want to do it on their own terms. That’s going to be really hard for certain products. I think Wistia is going to definitely win given their product mindset, and they’re really good at building product, so they’re going to come out with third product, fourth product, et cetera. They’re going to go the way of MailChimp and hopefully get to that size.

Some of the other companies in the space that do this are going to end up being like a Basecamp, which is amazing. I would love to be a Basecamp, just in terms of what the estimated revenue is, but they’re not trying to be a billion-dollar company, and you just kind of have to know yourself. Long story short, I think you’re going to see it, but you have to know what you want, and if you want to be a billion-dollar company, it’s going to be very hard not to raise money.

What content can do for you

“SaaS companies are the best companies in the world at monetizing traffic.”

Geoffrey: One of the biggest levers for growth for ProfitWell has been your content and your blog, which I’m sure many of our listeners will be familiar with. What is the ROI you’re finding content brings for your company?

Patrick: Content was our main growth channel. I don’t have pure ROI numbers for you, but here’s something to think about: We started exclusively focusing on the average number of pieces of content people were reading or looking at per week. The reason for that is because you can expect, for the average blog with social strategy and SEO mixed in there, the max average is about 1.6 touches per week. When you look at media companies, most of them are in the five to eight range. Every day, you look at Bloomberg or the Wall Street Journal or whatever your news of choice is.

We know that when people read our content, we get more qualified leads that then convert to money. But we don’t know exactly what that looks like, because our marketing tech stack is terrible right now. We just hired a head of growth. We didn’t have a marketing team until February this year. It was literally just me writing and doing all this content. We’re a 60-person company and I’m the CEO, writing and doing all the content; that’s a huge choke on the business.

Geoffrey: I think it was the exact same for Intercom. I think Des wrote 93 of our first 100 blog posts.

Patrick: Yeah, I’ve seen Des at so many conferences speaking and doing all these different content things. We’ve tried to figure out how to increase that max average, and that includes more content. We’re putting together three video and written shows per week right now. We’re trying to get to five by the end of the year. That volume we know increases our touches, and then we need to optimize it so can we increase even further based on distribution.

I don’t think we’re really great at distribution of content right now. We’re just kind of blunt with it: we just send it out and hope people share. That’s kind of how we think about the ROI. We know it increases down the path, so we just try to increase the top, because we’re already trying to figure out how to get more content people and media people to take this on. Eventually, we’ll probably get more sophisticated down the funnel.

Geoffrey: You’re kind of thinking at this stage that it’s kind of very much top-of-funnel, building the brand.

Patrick: Totally. There’s this interview I did the first month with a janky startup magazine. I was so excited because someone wanted to interview us about this thing we’d been working on. I thought of us as a product company that was wrapped in a media company, and that’s really what we’re trying to do: build a media company. If you look at media companies, they are the best in the world at content, because that’s their job. That’s their product. They’re the worst in the world at monetizing that traffic. Subscription and SaaS companies are the best companies in the world at monetizing traffic. They’re not so great at bringing traffic. I mean, they have to be pretty good, but they’re not as good as media companies. That’s kind of the mental model we work through. We have a bunch of data, but it’s hard to go through on a podcast.

Geoffrey: I think you’re going to see a lot more content-first, product-second companies. Obviously one of the challenges is at the moment it seems like every company has a blog, and pretty much everyone has a podcast. It’s such a crowded marketplace. Where do you look for the fertile territory here?

Patrick: Frankly, I don’t. Start looking at very niche podcasts that have insane followings. There’s a podcast on Mongolian history. You would think, how deep can Mongolian history can go? It’s got 80,000 monthly followers. And they’re not Mongolian; they’re all in the US. It’s fascinating.

I’m very interested in seeing what those types of people have done, because that’s where there’s the most leverage. It’s not like they spent a ton of money on ads and everything to drive traffic and built this inorganically. What you’ll notice with those types of people is they’re the ones who are focused exclusively on audience, and that’s what’s been lost in the world of content marketing, because it’s all been about using the blog for SEO, and social has its own strategy and its own channel.

We’re trying to take lessons from what Bloomberg or The Skimm would do, which is a modern take on media and building audiences. We’re thinking: “If you just subscribe to one show, that’s great. It’s going to come each week, but we’re going to have people who subscribe to every single thing we do, and that’s great, too. That builds that max average up.” I don’t know if we’re good yet. We’re still trying to figure this out. We’re pretty pumped to figure out the chokes in the process.

Geoffrey: I think in marketing, it’s always the hunt for the latest channel or the latest medium or the new book or the new podcast, but maybe there’s nothing wrong with the existing mediums and playbooks we have.

Patrick: I think the problem is that we’re not getting brand new channels. There hasn’t been a major channel since Instagram, right? Before that, we were getting at least one major channel a year, and there was this heyday back in the early 2000s up to 2010 where we were getting almost a new channel every single quarter. You were getting Google AdWords and then you were getting Google Display Net or Google Marketing, and it was like these giant things opening up. Now, we actually have the data that shows that channels are leveling off.

Most channels then go through these weird stages where they become new again. You’ve seen that with email: it’s become new again, and I’m sure you’re going to see this with content, because there are a lot of people starting to do episodic content. It’s just going to keep cycling. Who knows? I’m sure there are going to be major channels that open up, and you should take advantage of them. But we don’t really have the bandwidth to go hunt those new channels. We’re going to go after it, and as we built out the growth seam, I think we’ll definitely exploit some new channels. I’m very fascinated by looking at channels that have just been destroyed by just terrible sales and marketing people.

Geoffrey: Like direct mailers?

Patrick: Yeah. Maybe they’re not inherently terrible people, but they’re just terrible practices, right? I think cold email is terrible at this point, but we’ve found a way to be really, really good at cold email. We’ve found a process. This is some of the stuff that a lot of growth engineers have been working on, but we found a good way to do it. We found a way to do direct mail pretty decently. I don’t think we’re great at it, but we’re better than most.

It really just comes down to a lot of the things that Intercom talks about: create a good experience, treat people like people and don’t be so pushy. You’ve got to be a little pushy, because your targeting isn’t going to be 100%, so you’re inevitably going to have some bugs that aggravate people. Frankly, we still do some pushy tactics. We have too many popups and modals on the page and new redesigns. We’re taking a lot of those down, because the content volume is high enough now. I’m really interested in these markets and channels that people are doing really poorly, because most of the growth hackers have moved on, whereas I’d rather go really quality in those channels – or at least try.

Geoffrey: Everything old is new again, it sounds like. Patrick, thank you so much for joining us again.

Patrick: Yeah, thanks. This was great.