Any product serving two distinct sets of users is addressing a two-sided market. eBay connects buyers and sellers. Google connects searching consumers with advertisers. Social sites like Twitter and Facebook are also two-sided connecting consumers with advertisers.

What has happened of late with Twitter and Facebook is that developers have realized that, as neither a consumer or advertiser, they don’t figure in the plans of these companies.

This realization highlighted a potential opportunity: is there a significant two-sided market to be had by connecting application developers with end-users? Dalton Caldwell believes there is, and he is creating the platform App.net to do just that.

To succeed in a two-sided market there are 3 key criteria:

1. Positive Network Effects

There are 2 types of network effects, and each can be either positive or negative.

Same-side network effects are those where strength of one side has an impact on its growth. It can be positive—Facebook, for example, is better with all of your friends on it, so you invite them. It can also be negative: Facebook is less attractive to advertisers when all of their competitors have already saturated the market.

Cross-side network effects are when the strength of one side has an impact on the growth of the other. They can be positive: the more readers a news website has, the more attractive it is to advertisers. And they can be negative: the more adverts a news website shows, the less attractive it is to potential readers.

App.net’s fundraising alone shows that it has a positive same-side network effect on the user side at least, but possibly on both sides. Certainly it’s fair to assume that if they attract a significantly large user base, then they’ll experience a cross-side effect. One key differentiator for App.net is that, unlike any of their competitors, their entire user base has shown a willingness to pay for software. At a time when people are starting to ask hard questions about the returns on advertising on Facebook and Twitter this could prove quite important.

2. Correct Pricing and Subsidizing

There is almost always a money side and a subsidy side. The “subsidy” side is price sensitive, usually to the point where the ‘penny gap’ applies; any price is far too high. The logical conclusion of this is the tired “the users are the product” rhetoric we’ve grown so used to hearing.

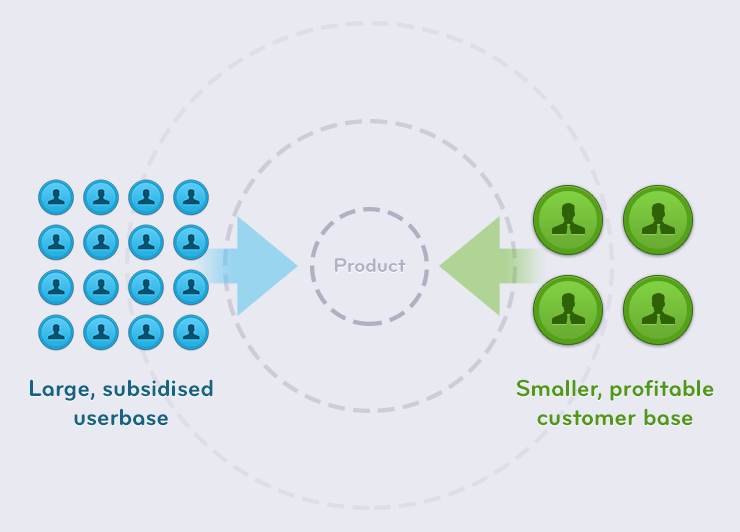

App.net has identified the developers as the money side (with initial pricing of $100 and $1000), and consumers as the subsidy side (with $50 per year pricing). This means that there’s no need to sell data, access, or impressions in the network. It also means that their consumer side is going to be tiny in comparison with Twitter.

This is a big problem if they plan to compete with Twitter in a winner-takes-all scenario. Which brings me to my final point…

3. Avoid Winner-Takes-All Scenarios

Winner-takes-all markets are high risk and high reward. The losers crash and burn while the winner is left with a lucrative legal monopoly. It’s best to avoid these kind of fights as a start-up unless you have a massive competitive edge capable of killing giants.

Discretion is the better part of valour, so it helps if you can see which markets will end up this way. For a market to be winner takes all, there are 3 conditions which must be met.

Are there strong positive network effects?

People go where people are. This is what renders Google+ irrelevant; no one is active there, so there’s no need to visit, let alone post any updates or invite your friends. If App.net is where I go just to hear from the 7% of my friends who don’t tweet anymore, then it could face the same fate as Google+. If everything happening on App.net bubbles up to Twitter anyways, it’ll also be in trouble. There needs to be a good reason for me to check and use App.net and that reason is only likely to be the people I want to communicate with. Answer: Yes.

Is there a high cost for using multiple products?

This cost can come in either time or money. I don’t use more than one phone or phone number as it’s both inconvenient and expensive. Both of those are zero-sum games.

However I have active Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Pair and LinkedIn accounts. Finding friends and cross-posting updates is easy so the marginal cost of each new network is small.

In short, this won’t be a problem for App.net. There is a solid precedent for consumers using more than one social network, so long as there is sufficient difference in either their format (e.g. Instagram vs Twitter) or audience (Facebook vs LinkedIn). Answer: No.

Is it difficult to deliver unique features?

Restrictions on what’s possible in innovation come from rules and standards around interoperability. This is why both laptop and monitor manufacturers bite their tongue and continue using VGA despite it being 25 years old. It’s why companies avoid standards and ‘open alliances’ in favour of rapid internal innovation. It’s why everyone who sets out to kill email inevitably adds a “Notify me by email” feature in their first update.

App.net have been praised for how open their platform will be. Will this restrict innovation? It’s too early to tell, but doesn’t look likely. Answer: Maybe.

Without three yes’s it won’t be a one horse race. App.net can succeed alongside Twitter, not instead of. Their definition of success is likely very different to Twitter’s.

What is success for App.net?

With over 12,000 paying users, including the most influential tech folks on Twitter, App.net have already taken massive strides forward. However, what is success for them?

By charging both sides of the market, they’re purposely shrinking the target market . App.net will always have a smaller user base than Twitter. However, as Apple have shown, the correlation between market share and profit isn’t clear cut.

There’s no reason App.net can’t be a very profitable venture with a far smaller user base than other online communities, while simultaneously doing no damage to Twitter. If anything, they could be doing Twitter a favour, by robbing them of the vocal minority who question and criticise every change they make.

It’s not for everyone

Those arguing that App.net’s model will only work for the tech community are missing the point. App.net customers don’t care, it works for them. Those saying that the business model can’t scale to Twitter’s levels are missing the point. App.net customers don’t care if it never gets to that level. This all reminds me of the days when I’d hear the rhetoric “OS X is only secure because it has a tiny market share”, to which I’d paraphrase John Gruber in my reply: “Does this mean I’m doomed to be always secure? Heavens no.”

App.net can succeed as a platform connecting passionate software users who are happy to pay for quality, with experienced software developers who enjoy being a first-class citizen of a platform. There are hundreds of challenges ahead, including sticking to principles, maintaining a brand, avoiding being enveloped by a client that simply combines App.net and Twitter updates, financing, and resisting big money advertisement offers to name but a few.

For fifty dollars it promises to be an interesting journey. I’m in.