Any startup founder knows the pressure of launching first. The belief is that if your competitor beats you to market, untold riches await them… while your company is now a dead duck.

This is rarely true. In fact, more often than not, it’s the other way around. 47% of first-movers fail, compared with only 8% of fast followers. As the phrase goes, you can recognise a pioneer from the arrows in his back.

First-mover advantage isn’t automatically bestowed unto the first product in a category. It’s not even guaranteed to exist in your industry and, when it does, it is fought for and earned.

It’s first winner, not first-mover

As Alan Cooper notes, being first to the market means precisely nothing. Being the first to enter a market brings opportunities which, when exploited, turn into advantages. First-mover advantages have a shelf-life and must be replaced with long-term differentiators.

There’s three types of first-mover advantage you can achieve:

1. Maintain a technological headstart

If you invent the category-defining technology, you have a potential head start when it comes to expert knowledge, usage data and customer feedback. Exploiting this advantage means playing your cards very close to your chest. You can’t release early prototypes, you can’t explain how anything works, or even let customer feedback be publicly accessible. All of this gives would be competitors a head start that you never had. This is what baffles me about Glass.

Google have chosen to throw away any possible advantage. The product is already out there in an embryonic phase. Not ‘live’. Not launched. Not secret and in-development. It’s out there for anyone to use and for Scoble to shower with. If there are any good use cases, you can bet that competitors have found them and are busy working out better ways to do it.

When your breakthrough product is launched your competitors will disassemble and reverse-engineer it. They’ll interview your customers and find out the true value of your product, the job it does best, and they’ll take all this data and start building the next generation of your product.

A year later they will all ship their 1.0. They will catch up to where you were. If you’re still standing there, you’re toast. This is when you need to be shipping your 2.0, leaving them in the dust, relegating them to be the company who always delivers “Yesterday’s Technology Tomorrow”.

That’s first-mover advantage.

2. Make defensive moves

Along with out-innovating your competitors, you can protect yourself with a selection of defensive moves. These are any tactics that prevent your opponents following in your exact footsteps.

Such tactics include things like:

- Exclusive partnerships with core component suppliers, e.g. pay a supplier over the odds to ensure that no one else can use their technology in your industry.

- Killing primary distribution channels, e.g. block booking advertising with your best performing networks or platforms.

- Winning patents to prevent your technology being directly copied and used in your industry, if not industry wide.

3. Lock up the early adopters

By signing up early adopters (i.e. those quickest to adopt or most influential in your space) you can make it near impossible for new entrants to get any foothold. This is most effective in the formative stages of a product category, and is achieved in two ways:

- Bribery: Simply give away free devices or accounts to the noteworthy people, and let them spread the word.

- Long-term contracts: If you’re confident your product is sufficiently desirable, remove mobility of customers with a nice 12/18 month contract.

How valuable is first-mover advantage?

In the HBR paper The Half-Truth of First-Mover Advantage, Fernando Suarez and Gianvito Lanzolla argue that the value of being the first-mover depends on two key factors.

Factor 1: the pace of innovation

The speed of improvement varies from category to category. Look at how email sat stagnant for 8 years following Gmail, in comparison with how quickly many social networks were born, bought, acquired and killed in the same period.

The speed of improvement also varies from era to era. For over a decade there was no worthwhile innovations in payments technologies, either as a business or consumer. But now in 2013 there’s innovation everywhere thanks to Stripe and Square unlocking the market.

In short, the pace of innovation is a measure of how much better the leading software is on a year to year basis.

Factor 2: the pace of market adoption

The speed of adoption varies from category to category, depending on their necessity, cost, ROI, and other factors. Some categories are instant hits, with 100% penetration within a decade, others can take 20 years before hitting double digits.

Combining these two factors gives us 4 outcomes.

Stable market, stable product

This is where first-mover advantages have most to offer in the long-term. If you grow your product at the same pace as the market grows, you effectively define the category, making it hard for new entrants to play your game. This is why people ask for scotch tape, hoovers, blu-tac and other category defining products.

Market ahead of product

In theory this is a nice place to be. Customers are rapidly consuming your product in increasing amounts without any significant innovations from you. The challenge here is to get it into the hands of every potential customer.

This is why it’s important to expand your addressable marketing, usually through multiple price points, multiple countries, multiple devices, etc. Failure to do this means you will be a local leader (e.g. the best daily deals site in North America, the best instant messenger app on Android, etc), which allows rivals to gain footholds elsewhere. Effectively you open the door to the Samwer Brothers.

When the market leads the product, there is a strong chance that first-mover advantage will be beneficial in both the short-term and the long-term, provided you address all potential customers.

Product ahead of market

When the technology is changing rapidly, and the market is slow to adapt to the product, being first is effectively useless.

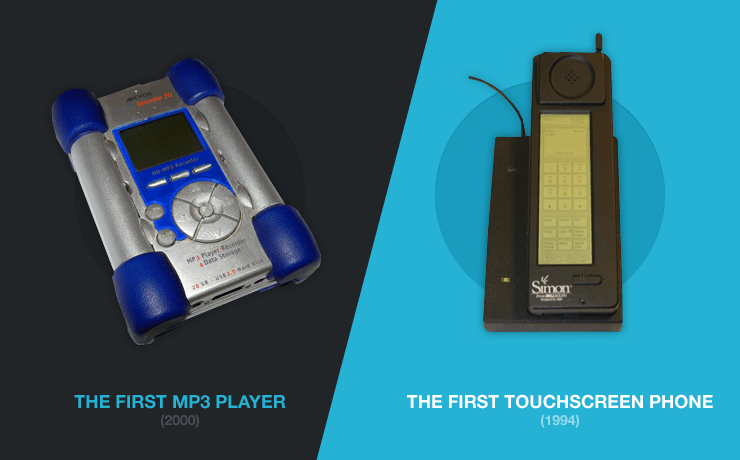

Every new technological advancement brings a new wave of competitors, and customers don’t care who produced the first, now laughably obsolete, product. Customers simply want the best available.

The tactic here is to refine the user experience of the product such that it appeals to more than just early adopters. This is what Apple did when they watched Saehan, Diamond Rio, HanGo, Creative Nomad, Cowon, and Archos all launch increasingly more advanced MP3 players to a slow-to-adopt public. Rather than getting caught in this mess, Apple waited until the technology was sufficiently advanced, and the market was sufficiently matured, before launching a product with the best experience.

Market & product both volatile

This is a dogfight. The technology is improving quickly while demand for the product increases rapidly.

A new entrant gets a short-term advantange here, as their slight improvement will gain a small foothold in the expanding market. WhatsApp, Viber, SnapChat, Line and others have all been #1 at some point only to be displaced. This is where the “building to flip” strategy can make sense, and also where investors need to distinguish short-term advantages from long-term strategies.

The following diagram sums it up, and should help you decide whether to rush to market, or take your time and get it right. Thanks for reading!