Design principles: what to do when nobody is using your feature

Main illustration: James Olstein

When we released our new messenger last year, we added the ability for customers to create rich, personal profiles so their users would always know there’s a real person on the other end.

The problem? Nobody was using the feature. Shortly after release, only 13–15% of customers had fully completed their profiles. Most were being partially filled in while many others were left untouched.

An example of a partial and fully completed profile

An example of a partial and fully completed profile

After talking with colleagues on our research and analytics teams, we uncovered two primary reasons for such low adoption:

- Visibility. The ability to create your profile was tucked away in low-visibility places throughout the app.

- Education. People were unconvinced of the importance of profiles in establishing a personal relationship with their customers.

One part of a wider solution

Profiles lived across many parts of the Intercom product which meant that we had to involve many teams to increase adoption. The growth team integrated profile creation into our on-boarding flow, while product gave higher visibility to profile editing within Intercom itself.

However, there was a huge opportunity to increase engagement by taking advantage of our mobile apps. Around 45% of teammates who talk with their customers (using our Inbox product) use either the Android or iOS app.

Getting started

For every new project, designers at Intercom create a simple list of high-level goals that reference the problem they’re trying to tackle. This helps guide you when thinking of high level solutions. Ours looked something like this:

- Raise adoption for users who have not completed or partially completed their profile.

- Educate users on the importance of public profiles.

- Make it easy for users to edit their profile at any time.

Thinking in systems

To start off, we took the profiles apart to help the team understand the system and to decide which specific components needed priority. That meant mapping out an inventory of parts, states, rulesets, etc. Here’s an example of something that would have been up on the wall in our war room.

Ideas come from anywhere

These system docs helped the team discuss technical constraints early on, and even at this early stage the engineering team was offering suggestions that the design team might not have thought of. For example, someone mentioned that we could draw from existing data sources to pre-populate certain components within the profile. Since we have a person’s name when they log into the mobile app, why not carry it over to the profile and save them the time of manually entering in that data?

After sketching out a few directions, we met with Emmet, our Director of Product Design, to get feedback and decide on next steps. Here were the four options that were presented:

The crucial ingredients here were disruption and education. We didn’t want this to be too easily dismissible, and we needed room to properly educate users on the importance of the profile and each of it’s components. However, we knew high disruption meant more aversion (i.e. users wanting to skip), so we wanted to keep the number of steps within any walkthrough as low as possible. In the end, we decided to go with the simple walkthrough option. Below are the decisions from the meeting. Progress!

Designing the solution

At this point, we had decided two things. We would add a simple walkthrough to our app on startup which would ask for any missing profile components to be filled in (disruption and education). Our third goal was adding the ability to “edit your profile from anywhere”. We decided to work within our current navigation pattern and add a simple edit icon within the nav drawer which would trigger the walkthrough.

Note: One of our core values here at Intercom is “think big, start small”. We had been planning a navigation update for a while at this point. Moving from the drawer to the tab bar would be great for a variety of reasons, but would have been a ton of effort engineering wise at the time and we needed to ship fast.

Current navigation (left), planned navigation (right)

At a system level, we established three states for users which would dictate their position within the walkthrough. From the chosen high-level direction, we knew that the the flow would consist of three primary steps (see diagram below) which we wanted to make as easy and lightweight as possible.

Walkthroughs are pretty straightforward in terms of system design. They are a fixed pathway from beginning to end, but the logic gets more complex when taking user states into account. We’d want you to skip straight to the most relevant part instead of forcing you to go through the entire walkthrough. It’s also very important to consider platform specific steps such as camera permissions. Not every step is a new screen.

Again, these diagrams were printed out and put up in our war room. Engineers would often be at the wall scouring through the flow, and a few times they would spot an edge case that would require us make changes together.

Final flow for the walkthrough

Execution

By now we had the skeleton to start fleshing out each part. Visual and interaction design happened simultaneously, with the knowledge that we’d continue to tweak visuals as we build. We’ve found that finalising the details around any complex interactions or animations should be done as soon as possible (which is why high fidelity prototypes are great). It’s much harder to change these later on as opposed to visual design tweaks such as updated assets, colours, etc.

We used Framer JS as a way to prototype early interaction ideas, discuss with engineering and agree on what could be done. Here’s an example of our final iOS flow after around 12 prototypes.

From a visual design perspective, our mobile apps already followed closely to our brand. Any new designs need to maintain that language as well as reuse any patterns needed. We worked with our stellar brand design team for illustrations on the intro and confirmation screens.

Content was crucial to the education problem. We needed to explain why profiles were important in a concise way. Design worked closely with Elizabeth McGuane, our content strategist, to create a more compelling experience and help users understand why a great profile matters.

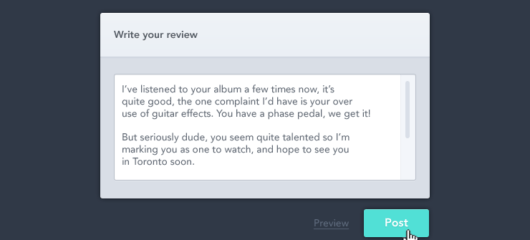

Example of our content strategy doc

Testing and tweaking

We were conscious of the disruptiveness of the walkthrough and how many people would most likely skip it, even after adding the option of reminding users to complete their profile later. Setting up metrics for component and overall completion was key, as well as allowing for a beta period to adjust based on results.

For our first beta, our initial completion rate was quite low, especially on Android. We made a variety of tweaks to the design, such as removing prominence from the remind me later button, altering layout and tweaking the content to be more playful and less instructive.

Building a feature people actually use

Over about a week of quick tweaks and monitoring, the completion rate increased dramatically. Thanks to the input of multiple teams, we saw our overall profile completion rate jump from 14% to 46% within a month. The mobile walkthrough played a huge role in this push. We were also left with a concrete set of takeaways that we could apply to our next project:

- Make sure the problem is crystal clear to all stakeholders, across teams

- Ground the problem in research and metrics, use high level goals to guide your solutions

- No matter what you’re building, think big and start small

- Design should work with engineering early and consistently to grab ideas and validate concepts

- Interaction design should be nailed as soon as possible as it’s much easier to tweak visual designs while building

- Know your metrics of success, track the success of your solution and make sure there’s time to tweak

Following a clear, logical process like this vastly increased our chances of producing a feature that people actually use. It may seem like a lot of detail at first, but once you establish the habit it becomes second nature.