People leave managers, not companies – 4 ways to better support your team

Main illustration: Geoff Kim

Across the US, people are quitting their jobs in record numbers.

This year, it’s estimated that approximately one in four people have quit their jobs, and those positions are remaining open for much longer than expected. Countless theories have tried to explain the “Great Resignation” we’re experiencing, but none have managed to pinpoint an exact cause.

That’s likely because there isn’t just one cause – the pandemic has pushed underlying issues to the surface, triggering a widespread re-evaluation of what’s important in our work lives. One thing that will always be on that list, however, is good management.

It’s not me, it’s you

The data suggests bad management is a real and significant issue. According to data from DDI’s Frontline Leader’s Project, 57% of people have left a job to get away from a bad manager. In fact, Gallup found that 70% of the variance in employee engagement depends on the manager.

Yet few managers ask themselves the hard questions: am I the reason people are leaving? Was it because of something I did, or something I didn’t do? In my experience, managers suffer something akin to the Dunning-Kruger effect. They assume they’re not the problem, their employees are.

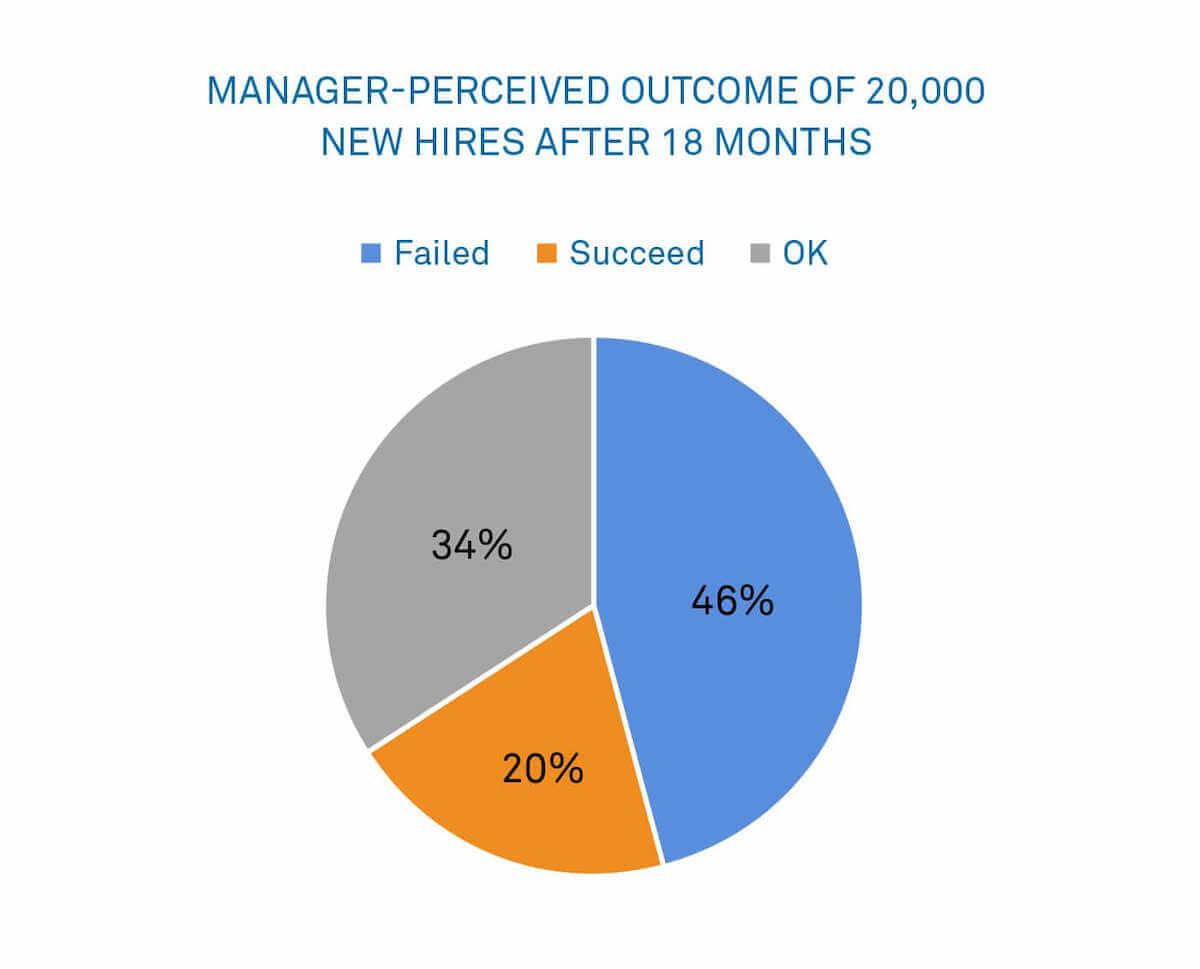

Just look at the data to see where managers are laying blame. A survey of 5,247 hiring managers who’d hired 20,000 employees said that after 18 months 46% of newly hired employees failed and only 20% achieved success.

According to the managers, the most common reasons new employees failed were:

And what was the biggest takeaway for managers interviewed? They needed better interview processes to weed out the failures before they joined their teams.

To any rational person, this makes no sense. The common denominator isn’t the 46% of employees. It’s the managers. Is the problem really that half of the people couldn’t learn or care about their new job? Or was it that a smaller number of managers overestimated their own abilities to teach, connect, and inspire their new hires?

I’ve led teams of engineers for almost a decade but when I look back at my own management career I regularly thought I was a “good manager”, at times even a great one. I attributed any problems I encountered to the people I managed rather than myself. Looking back now it’s clear I was actually a blindingly naive, over-confident, under-skilled, inexperienced manager who made lots of mistakes.

This management overconfidence is a trap I see many others falling into, but it can often be avoided by following a few of the steps below.

1. Always ask for advice

As a software engineer, no matter how senior you are, you always seek code reviews before deploying new code to production.

The same is true for managing people. You should always be asking for peer review on a people management problem before you take action, whether that’s from your own manager or your HR team. The bigger the potential consequences of your action, the more thorough you should be about getting help and peer reviews before taking it.

“If there’s someone on my team who’s not performing as well as I’d like, I ask for help on how to coach them differently”

Now, when I have a performance review to write I talk it through with my peers or my boss before delivering it. If there’s someone on my team who’s not performing as well as I’d like, I ask for help on how to coach them differently. You can do this for pretty much everything, people-related or not, and get a better outcome as a result.

The moment you think you’ve really nailed your management skills is when you’re most vulnerable to failure.

2. Don’t blame, own

Ownership is an important part of how we do things at Intercom, and it applies as much to managing people as it does to engineering. It’s not in our culture to say “that’s not my problem” or “that’s not my fault.”

Yet as a manager it’s all too easy to abdicate responsibility and blame the person on the other side of the table when they are not doing as well as you’d like. The fact is that every person you manage is different. Just because one management style worked with the previous three team members and not with the person in front of me doesn’t make it their fault. Like a good sports coach, managers aren’t judged on the performance of individual players, but on the team’s effort. The onus is on you to make sure you’re catering your management style to suit each team member.

“I often discover the best next step is not giving ‘constructive feedback’ to someone on my team about their mistakes; it’s requesting feedback on how I can better support them in future”

I have to constantly check myself to make sure I’m taking ownership for the relationships in my team and doing everything I can to make things better. Instead of assigning blame to others when things go wrong, I try and figure out my own role in the situation. What are the things that I have done, or not done, that have contributed to the problems at hand?

If I have any trouble identifying these, I go back to step one and ask for advice from my peers. After this exercise I often discover the best next step is not giving “constructive feedback” to someone on my team about their mistakes; it’s requesting feedback on how I can better support them in future.

3. Give feedback with empathy

Giving feedback is your most powerful tool for growing your people and your team. It’s also one of the hardest to get right. Do it wrong, and you’ll turn your most proactive tool into something destructive.

Before I deliver any feedback I set aside some time to understand how the other person might receive the feedback. Is it likely to be high-fives all round? Or might they feel hurt or upset? Try to pay particular attention to the wider implications of the feedback you’re giving.

Candid feedback could motivate a seasoned engineer looking to step up to the next level, but dishearten a recent hire who’s finding it hard to settle in. Don’t give feedback in a moment where the tone or timing isn’t right. Use your emotional intelligence and empathy. You can always save your feedback for another time, and a more private or less stressful setting.

4. Savor your success

One of the best things about being an engineer at a fast-moving company is the feedback loops. You can prioritize, design, build, and ship into the hands of users – all within a week. These feedback loops are fuel for your team’s morale; they have a positive influence on your team’s productivity and power each team member’s happiness and job satisfaction.

“It’s easy for managers to get caught up with looking forward all the time, or focusing exclusively on problem areas”

Unfortunately, as your company grows, those feedback loops can get longer and longer. Added to that, managers in larger companies tend to have their eyes further out on the horizon, planning for a few quarters down the line – it’s easy for managers to get caught up with looking forward or focusing exclusively on problem areas. In these situations, it’s more likely that your team’s shields will drop. They’ll feel under-valued, just another cog in the machine.

Celebrate your team’s successes and let team members know they’re making an impact. You don’t have to hang bunting from the ceiling. It could be as simple as giving someone detailed, timely feedback on something they did really well, passing along some positive feedback you received from your boss about your team’s recent work, or praising someone’s work in a Slack channel.

Great managers build great companies

When you stay humble, ask for advice, own rather than blame and give feedback with empathy, you’re on the path to being a good manager. But as we’ve seen, success as a manager breeds complacency, and it’s all too easy to fall into bad habits of overconfidence.

Once you think you’ve really nailed your management skills, that’s when you’re most vulnerable to failure. You need to constantly revisit what it takes to be a good manager, or risk losing your best people for good.

Can you see yourself working at Intercom? We’d love to talk to you – check out our open roles.