Airtable’s Andrew Ofstad on maintaining simplicity at scale

Product complexity is one of a growing startup's many challenges. How can we offer users more without making it harder for them to find success using our product?

https://art19.com/shows/inside-intercom/episodes/fa715310-d728-4969-901c-110303ceb697As a new product manager on what had become a convoluted Google Maps product, Andrew Ofstad was challenged with solving this problem, and led a product redesign with one core aim: Restore simplicity to the product without sacrificing capability.

Today Andrew is the co-founder and chief product officer at Airtable, a collaboration tool that make technical databases accessible and easy to use for less technical folk. It’s used by everyone from product and marketing teams to cattle farmers and filmmakers.

My chat with Andrew covers why complexity slowly creeps up on product builders, the way his team at Maps pared the UI back using first principles, how that experience helped him keep the UI simple for Airtable, a fundamentally complex product, and much more. If you enjoy the conversation check out more episodes of our podcast. You can subscribe on iTunes or grab the RSS feed in your player of choice. What follows is a lightly edited transcript of our conversation, but if you’re short on time, here are five key takeaways:

- Writing software that is tied to hardware releases, like Android, is reminiscent of shipping a CD-ROM. It’s not like most other projects in software today where it’s iterative and you’re constantly shipping features, .

- Prioritization is the most important thing you do as a Product Manager and to do it well you need a good mental model of what your users are doing with the product first.

- The lesson of Google Maps in 2010 was that an ambitious team will keep building and shipping new features but at a certain point you need to take a step back and look at it with fresh eyes.

- Airtable is trying to recreate the immediacy of products like spreadsheets or Maps where you can manipulate the data directly, but in something that has more structure like a database.

- The danger of eating your own dogfood is that you can lose touch with how your customers are using your product which may be for vastly different use cases.

Adam Risman: Andrew, welcome to the show. Could you give us a quick rundown of how you got to where you are today and the problem you are trying to solve with Airtable?

Andrew Ofstad: I started my career at Google as part of the Associate Product Manager Program, which was started by Marissa Mayer. Basically they take new grads and throw them into the deep end as a product manager, so it’s a great opportunity to learn a lot quickly. My first project was Android. This was in 2009, when Facebook and Twitter weren’t interested in building Android apps, so the actual Android team was responsible for doing that, and I was the Product Manager for those two social apps. It was a lot of working with Facebook and Twitter, getting their assets and actually designing and building those apps. You do one year on a product and then you rotate to another one.

My second product was Maps. I was always really interested in geography and always loved maps, so I was super excited to work on it. From the ground up we took Maps and redesigned it. At the time, back in 2010, Maps had become super complicated. There were all these teams working on different features, and the mandate coming down from Larry (Page) and Sergey (Brin) for Maps is to organize all the world’s information, at least geographic information, and so there were a ton of information – maps, imagery, business information, street instructions, etc.

Maps had become really cluttered and complicated; it wasn’t a simple interface anymore, so we had this great opportunity. There was a team in Seattle that developed this new technology where you could actually render the maps in the browser using webGL, and this was a nice excuse to appropriate that technology and redesign Maps from the ground up. That was my project.

While I was working on that, I got the itch that led to Airtable. My friend Howie and I had always talked about doing a startup together, and I had always been interested in creative tools that let normal people do things that previously only experts or programmers could do. So I prototyped a lot of products where you could build web pages and simultaneously Howie had sold a company to SalesForce and was a Product Manager there. He saw that a lot of business tools were reinventing the wheel and becoming simple databases with some simple views and logic and workflow on top. One of the most important things he also saw at SalesForce was the ability to actually customize these tools to fit your very unique workflow.

The problem is if you’re adopting a business app, a lot of times they’re very rigid, inflexible, and you can’t really make them fit your very specific use case, so you’re either stuck with a very rigid application or you have to build your own and need somebody that understands databases to configure something like SalesForce for example. Or you need a programmer to build a custom app. The other side of the spectrum is just using something like a spreadsheet, which wasn’t really intended for being used for that use case and was built for number crunching and financial modeling.

There wasn’t really a tool where as an end business user, you could really build a good, internal application to manage a very specific process of workflow. We wanted to build something that was easy enough for anybody to use, and that’s where we aligned with Airtable. We started doing a lot of prototyping, built an initial demo, started showing that to people, getting a lot of feedback and refining that over time. We’ve grown the team and the product, and it’s been a good adventure so far.

The early days of Android

Adam: You weren’t just with Android in the nascency of your own career, but in that of Android itself. Looking back at that experience, what sticks with you today now that you’re a founder yourself?

You had to build like the old days when you were shipping a

CD-ROM.

Andrew: There are a few things that made Android really interesting. You’re shipping software that goes along with hardware, so there are very tight deadlines where every six months you have all these carriers and partners expecting the next version of Android that they’re going to ship on their new phone. You’re tied to a hardware launch, which is a very rigid timeline. Compared to most other projects in software that we see today where it’s iterative and you’re constantly shipping features, you basically had to build like the old days when you were shipping a CD-ROM. That drove a lot of urgency, but also excitement in the team, when you are given this mandate to build this very ambitious new release and you just kind of have at it.

The other thing that really made Android interesting was the neck and neck race with Apple. I joined before the Droid was released, and that was the inflection point for Android. At the time it wasn’t really clear if it was going to be a huge success. There wasn’t a lot of adoption and it was right before an inflection point, so that urgency of competing directly with somebody also made things very interesting and made it a very fast-paced team to join initially.

Some of the lessons from that you can apply to any company. At any startup you’re racing against the clock and you only have so much runway, you always have competitors and you’re always fighting the status quo as well, so there is that same sense of urgency you need to convey. As much as you can take the actual urgency of what we’re doing and the problems we’re trying to solve for our customers and communicate that to the team that’s actually building the feature, he better it is as a motivator. It actually creates the same urgency you see in a very hard deadline on Android. We try to do that as much as possible and really tie the people that are working on the product back to the customer who are really demanding these features and really excited to see them.

Adam: What do those rigid deadlines teach you about prioritization, something that’s such a huge challenge for early stage startups?

Andrew: Prioritization is pretty much the most important thing you do as a Product Manager, and you obviously want to be working on the most important things that you can ship in a given time period. But it’s hard to figure that out before you actually start diving into it. It’s a matter of figuring out the bare essentials that you absolutely have to have and then stack ranking those. It’s also figuring out what trade-offs you can make – are there a few shortcuts for things that are less important?

The danger in that is that a lot of times, you can sacrifice a lot of quality product decisions – you throw things out that would make the product very delightful or otherwise would be worth the investment just to squeeze in these other few features that might not be used by most of the users. The first thing is understanding the use cases and having a feeling for that 80/20 split, where you know what people are doing with the product most of the time and stack rank the use cases. Figure out how to make the experience completely awesome for the 80% and then afterwards we can fit in the 20%. You need a good mental model of what your users are doing with the product first, that’s the prerequisite for any prioritization. After that, it’s all about making sure that for those experiences everything is really simple and really delightful and as high-quality as possible.

Google Maps: When products grow overly complex over time

Google Maps in 2010 vs 2017

Adam: Speaking of making things more simple and delightful, in 2010 you moved over to Google Maps. What was the state of Google Maps when you got there?

Andrew: Google Maps in 2010 was a pretty amazing product. If you look back to 2005 when it launched it was also a ground-breaking product, because at that time everything was a full-page reload. You go to Mapquest and you press a button to move the map over and the full page refreshes. It didn’t have any interactivity. In 2005 Google Maps launches and you’re able to reach out and grab the map and drag it. You have this interactivity, which made it amazing. Even though it didn’t have the same feature set as Mapquest, it basically went beyond that because it was so easy and efficient to use.

The team had focused on getting a lot of information into Maps without rethinking

the UI.

Between 2005 and 2010, Google had invested a lot in Maps and added a lot of information to it – imagery, street view, business information, satellite view, all these aerial photos. The team had focused on getting a lot of information into Maps without rethinking the UI to accommodate all the different information. There were teams distributed between New York, Seattle, Mountain View and Zurich who were building all these features disparately. In a lot of ways it reflected the organization, where there are all these really smart teams doing amazing things and pouring these great features into Maps, but there wasn’t really a thought process around how they’re fitting into the whole.

Adam: So you have organizational complexity that’s essentially fueling product complexity?

Andrew: That was part of it, and it was a slow buildup to that complexity. It was like boiling a lobster. It was slow increments over time and nobody realizes if you don’t look at it with fresh eyes that this thing is really complex and cluttered. An ambitious team will keep building new features and keep shipping things, and that’s great. But at a certain point you need to take a step back and look at it with a fresh eye.

Simplification from first principles

Adam: Walk me through your process in this unique challenge. Did you begin by paring things back or start from first principles?

Andrew: We actually started with first principles, which helped a lot. We had a great excuse to do that, which was a team in Seattle who was building a completely new way to render the actual maps. The way it worked before is we’d render these map tiles in the server and send them to the client as images. This team found a way to render the map directly in webGL in the browser.

We started thinking of all these cool things you could do with that. You could change the map every time you click it or you could show animations in the map. We could render the map however we wanted for any different search or context and make it interactive. This gave us an excuse to rethink Maps from the ground up around that new technology, and I think that helped a lot as opposed to paring down.

The other thing that helped is we didn’t say that on a certain deadline we’re going to completely eliminate the old Maps and replace it with a new one. That would have created the problem that every team starts flooding to the new Maps team to add all these new features and pretty soon you’re right back where you started again. So we had the existing Google Maps and we spun this project as the new Google Maps, which you can opt in to try. It was this beta thing, and that led us to keep it constrained to the most important use cases in the early days and build up the components that we needed to really make those use cases shine.

Then organizationally it helped because slowly you wrap in your other groups like the Directions team and it’s not like everybody piles on at once. It’s a slow trickle of people moving over to the new thing. It helped a lot for us to start with just a prototype and scale it up from there and slowly get more people involved and excited about it, as opposed to having a completely separate team, which just suddenly launches a product and replaces the old one.

Adam: As you’re getting more and more people involved, what types of constraints did you have to put in place to make sure this iteration of Maps didn’t get too bloated?

Andrew: Philosophically we wanted to limit ourselves to a few UI components. We wanted to make sure it was mostly about the map and not just a bunch of chrome around it. We really focused on that aspect and took a lot of inspiration from mobile apps at the time. We saw a lot of really simple design for complex products in mobile apps and we took that as inspiration for the web app that we were working on. It was taking the constraints that you have on mobile, like a small screen and then applying that to where you actually do have a lot of space. We wanted to create this simple experience that covers these core use cases really well and does it in a really interactive and efficient way for the user but make sure that we’re following these constraints.

You have to find the pieces of UI that are simple yet expressive.

The other important thing is as you’re designing this you have to look at all the use cases and over time think about how they’d fit into the larger pattern. You can’t just build a one-off feature for a very specific use case; you have to find the pieces of UI that are simple yet expressive. An example on Google Maps was the search box. It’s a very expressive thing where you can search for anything in the world and it should just pop up on the map, or if you do an auto complete, you can surface directions from that – keeping things contained to these expressive components. Imagery, for example, always reflects the current context of the map so if you search for something, the imagery would reflect exactly what you searched for.

We took a lot of inspiration from mobile apps where things are very contextual and you tap on something and suddenly the UI becomes about whatever you tap on. We don’t just show everything at once, which is a lot of what we were doing before – where you just turn on the map layer or the photo layer and there would be a ton of photos on the map. We wanted to make it contextual so every part of the UI always reflected the thing you were currently focused on in the context of the current map or search.

It takes a lot of discipline of being very intentional and stewing on a feature for a long time, running through the use cases in your head and then making sure you’re not trying to throw everything into it. Going back to building from the ground up versus paring down UI, it’s a lot easier to go from the ground up and make a really clean UI for something that’s very complex.

Adam: You mentioned taking inspiration from mobile apps at the time of this project, but today, what do you see as a model product that’s very sophisticated in terms of capability but has managed to keep their UI very simple?

Andrew: I was always into creative tools and I really like Sketch. Figma followed in their footsteps as well but if you look at the status quo at the time it was Adobe tools like Photoshop that were super complicated. You can do a million things with filters, image processing, etc, but what most people were actually using it for was designing web apps. Sketch saw that and realized that basically you’re just trying to design web pages, so you want the design tool to reflect what you can do in the actual medium, which is the web. They pared that down and made it contextual where you can select objects and the UI changes to show what you can do with that exact object rather than showing all the controls at the same time.

I definitely took inspiration from tools like Sketch in the Airtable days after Maps. Today I still think they’re doing a great job.

Applying Google lessons to startup life

Adam: Looking at the work you did with Google Maps and what you’re doing with Airtable today, one of the biggest crossovers is that you have made the content the UI. What other lessons from your Google Maps experience did you apply as you got Airtable off the ground?

Andrew: We actually called that Maps project Tactile Maps, because we wanted users to feel like you could reach out and touch the map, click on the place, drag it, move it, etc. For Airtable, we wanted to make it about the data as much as possible. When we looked at other database tools out there like Access, when you first started with it, you’d have to go through all sorts of configuration, set up this schema, and do all this meta stuff around actually setting up something that you can put your data into. The reason people love spreadsheets is you can just pop it open, there’s a grid, and you just start entering information. You can easily, directly manipulate the data itself. You can bulk select, delete things, change colors, copy-paste, etc. There are all these ways that you can reach out and touch the data.

With Airtable we wanted to recreate that immediacy of something like spreadsheets or Maps, where you can reach out and touch the data and manipulate it directly, and bring that over to something that has more structure like a database. That’s one of the main lessons: making it as easy as possible to manipulate the data quickly and get down to working directly with information.

Adam: You mentioned the spreadsheet metaphor. With horizontal products like yours, which have such a wide array of use cases, how important is it to have a metaphor like that to communicate what a product can be used for? How has that helped as you’ve brought Airtable to market?

Andrew: Airtable is fundamentally a complex product and something that’s a bit difficult to wrap your head around without actually seeing it. The spreadsheet metaphor helps us a lot because when people see a grid they expect it to behave like a spreadsheet, and we support all of the things it can do.

One thing we’ve learned is being able to show the product in the context of data that the user actually understands goes a long way. When you’re starting in the onboarding flow of Airtable, we have you pick a few example templates, which are hopefully relevant to you, and then we show you those templates in Airtable. We show the grid, which looks like a spreadsheet, and people understand all the patterns they’re familiar with there and we support all those patterns.

But we also want to show the differences, which is one hard part if you rely on an existing metaphor. A lot of times people expect it to behave exactly the same, but when you actually show data, it communicates pretty clearly what’s going on. One of the main differences between Airtable and a spreadsheet is that each column is a specific type and each record is like an object you can expand out into a form. When people see columns of data that all look the same whether it’s a colored select drop down or attachment or text or link to another record, that helps to convey this is a grid like a spreadsheet and it supports all its interactions, but there are also these key differences that you should be familiar with. The data really speaks to that and lets you play around with it.

Using your product to build your product

Adam: One of Airtable’s key use cases is product teams. Are you guys using Airtable to build Airtable? And if so what unique insights does that give you into your product?

Andrew: We use Airtable for everything from our product roadmapping to our marketing editorial calendar, where we we’re planning our next blog posts and feature launches, to tracking our bugs. Pretty much everything where we need to track something for our product development or marketing we use Airtable. In the early days we were just building the product for ourselves.

Adam: So you knew you were really solving a problem there?

Spend a lot of time talking to customers who have use cases that are far removed from yours.

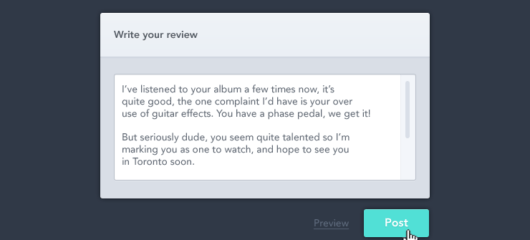

Andrew: Exactly, so as early as possible we started using it for all that stuff. But there’s some danger that you lose touch with your customers if your customers are using it for vastly different use cases. It’s important that if you’re using it internally all the time to also spend a lot of time talking to customers who have use cases that are far removed from yours. We have everybody on the team do customer support rotations, where they’re talking to customers through Intercom, and it really drives a lot of innovation.

We have hack days and people always build the features they actually want to see in the product from using our databases, but it’s also important to make sure everybody’s exposed to everybody else’s use cases to make sure that we’re not just building it for ourselves.

Adam: As Chief Product Officer, are you still interfacing with customers at this point?

Andrew: We do a lot of big customer tours where we’ll go to New York or set up a bunch of things in San Francisco and go to one meeting after the other to see how people are using the product, where there are roadblocks and how we can help. I do a lot of that. It’s the main job of a product person to try to understand the customer and translate that into the most important things to work on next, so it’s definitely important and something that I always want to stay involved with.

Finding first customers

Early Airtable traction on Product Hunt

Adam: You guys have over 30,000 companies using Airtable now. How did you get those first several? What were you doing on the front lines in the early days?

Andrew: In the early days we had a half-functional demo that we showed to friends and investors. We’d work on Airtable all day then the next day we’d do a bunch of user studies and show it to people and get thoughts. Our first real customer was a non-profit called ScholarMatch in San Francisco. My co-founder Howie had worked with them before and knew the Director pretty well. We were showing her a demo and she’s says, “We’re looking for a way to track all our students, donors and events.” They were looking at some sort of expensive SalesForce integration or building their own custom software. We showed them the demo and she asked when they could start using it. We’re weren’t really ready for that yet, but we set them up and they were our first customer.

It’s a really complicated product so it took us a while to get it to what we consider the V0, where it’s a complete product. Initially it was people who heard about us though Product Hunt or Hacker News or people we knew directly and it spread from there. Now it’s purely word of mouth. All these use cases where we’ve seen a lot of adoption, like video production and marketing teams, word just spreads within those verticals organically. It from pure enthusiasts who love the technology to people where it was solving a very acute pain.

Horizontal use cases

Adam: Like a lot of horizontal products, you’re bound to have some very unusual or unexpected use cases. For instance, you have farmers tracking their cattle on Airtable. What’s the most unique or surprising use case you’ve come across, and did it teach you anything new or different about your product and its potential?

Andrew: That may be the most surprising thing, the number of cattle trackers that people have built. There’s actually a vertical piece software called CattleMax. It’s just a database app for tracking your cattle and everybody’s switching from CattleMax to Airtable now, which is awesome.

People use it for work, but they also use it for personal use cases and have a lot of really cool, unique things they’re tracking in Airtable. People will track all the characters from a comic book in Airtable and have these really cool images of it. We’ve seen everything.

Adam: Well with a spectrum of use cases, you’re going to get feature requests that are all over the map. I’m sure you’re saying no to more and more things everyday. How do you make sure that you maintain simplicity over time and don’t just become another bloated project management app?

Andrew: Especially on a horizontal product, from day one you have the problem of people asking for all these random things that if you throw it into the product, it’s going to apply to their very niche space, but it’s going to be clutter for everyone else.

We think very carefully before we build a new feature, and we have this concept of simmer features where for these big things we know we’re going to do eventually, we let them sit there for a while and we think about it and just keep it in the back of our minds. So as we hear more and more use cases from more and more verticals, we can see how they fit into that and figure out a way to take that set of use cases and build a future that is generalized enough to kind of adapt to all of them. So we take a long time to actually think through a feature if we know it’s going to be like a big component.

The other thing is building in a modular way so that for different use cases you can like add or remove pieces. One simple example is that in Airtable, you have columns in your tables. Each column is a different field type, so you can add any different field type you want and you can combine them in different ways and you have this combinatorial explosion of complexity, where you can customize and fit a lot of different use cases by adding different structure to the table.

Then we have this other modular concept of views where a view is a different way you can present that data, so you kind of have like your raw table with records, which are just configuration of different fields, and then we have different ways you show that. It’s these modular components you can combine in different ways and mix and match. Basically if you’re using our table for one case, you can use these five fields together and these two views, like a calendar view and a gallery view, but you don’t have to see a button for the map view and all this other stuff that’s not relevant to your use case.

We try to think in terms of expressive components that you can kind of mix and match into your own application. At the end of the day, we think of Airtable as an application builder. More and more we’re going to tackle different layers of that stack, where you can basically build like a full-fledged application. But there’s a lot of complexity in that so you have to build features that are flexible and generalizable but still have a cohesive metaphor behind them.