Lean UX author Jeff Gothelf on why design must have a seat at the table

In an era when it seems like the designer sits near the top of the tech industry pecking order, it’s hard to imagine a world in which design is an afterthought.

If an organization’s founders aren’t designers and don’t come from a background where well-designed products played a key role in their lives, it can often be the last discipline to be brought onboard the team. Author Jeff Gothelf sees this all the time in his work as a consultant for medium- and large-sized companies, and it inevitably leads to a culture clash where designers feel unvalued. But if these design leaders can seize the opportunity of having a seat at the table, they can assemble an interdisciplinary team that solves real customer problems, proves their worth, and ultimately changes the future of the company and the products it delivers.

Jeff is the author of Lean UX (which teaches how to rapidly experiment with design ideas) and the co-owner of Sense & Respond Press, a publisher of short, actionable books for busy leaders. He joined me for a chat that ranged from strategies for making design part of a company’s DNA to the lessons we can learn from the human cannonball at a circus.

Short on time? Here are five quick takeaways:

- You must establish deep empathy for the customer. Just because you understood your customer when you started the company doesn’t necessarily mean that those needs and those pain points are the same today – or that you’re meeting those needs in the same powerful way you may have been doing a year ago.

- In companies without a design DNA, Jeff recommends creating an “in-house startup,” where a small design team innovates around a challenge and proves its worth by positively impacting customers.

- Focus on outcomes over output. Instead of looking at product delivery as the metric for success, switch your focus to changes in customer behavior as the sign of whether your efforts were truly successful.

- Test your assumptions, always. Learn from the human cannonball that Jeff worked with, who was seriously injured when circus employees followed the same old process they always had, even though conditions had changed.

- You have to run your business with enthusiastic skepticism: the burning feeling that you can always be doing something better, and you’re excited and enthusiastic to find out what that is.

If you enjoy our conversation, check out more episodes of our podcast. You can subscribe on iTunes, stream on Spotify or grab the RSS feed in your player of choice. What follows is a lightly edited transcript of the episode.

The evolution of a career

Dee: Jeff, thanks a million for joining us on the podcast today. Tell us a little bit about yourself and how you came to be an expert on everything from agility processes to product design and general digital transformation.

Jeff: I started my career like anybody else back in the web 1.0 days doing whatever we could to get websites up online, which was HTML and a little front-end design. What’s interesting is that as the complexity of the web increased, the complexity of the work that we were doing increased. And so I moved to specialize a bit more initially in information architecture and then user experience design and then product management. I hit a critical point about 10 years into my career. I realized that despite being a designer primarily, I wasn’t really designing anything. I was writing specifications documents. And on a good day, 50% of those spec documents would get implemented – which meant that on a good day, 50% of my work got thrown away. On a bad day, a lot more of it got thrown away. I wasn’t willing to continue down that path if this was the way it was going to be for the next 10 years.

Luckily for me, I found myself in a position where I was leading a design team in New York and an organization that was transitioning from waterfall software development to agile software development. My responsibility was to build a design team in that new agile way of working. This was about 12 years ago, and back then nobody had a good answer for how to do this. Lots of people had bad answers and failed answers about how to do it. So we set out to solve this issue, and we talked to the people who had tried and not succeeded and we learned a lot of things, a lot of anti-patterns, and we iterated. Then about six months later, the team and I had figured out something that worked for us, and I began to write and speak about it, and all of a sudden, I got offered the opportunity to write a book about it. There were some other folks who were doing a similar kind of work. I met Josh Seiden, who became my coauthor, and the book did really well. Lean UX was the book, and it changed what I was doing for a living. People stopped asking me to design software and said: “Jeff, we’re also having all these same problems. Come teach us how you guys did it at the Ladders.”

So that’s when I started doing. I started consulting and teaching and training and speaking about this. And what’s fascinating is that over the years, the scope of that conversation has moved, has grown to be not just a tactical product-team-level process of fixing and improving, but of organizational improvement as well, because you have to build the kinds of cultures and leadership teams that support this way of working, or it doesn’t work. So today I work with product teams to help them build better products, and I work with leadership teams to help them build the cultures that build better products.

Staying agile as you grow

Dee: What sort of companies are these teams based in?

Jeff: The companies I generally work with are large- and medium-sized companies. More often than not, they are what we would call today traditional, established types of businesses: brick-and-mortar retailers, banks, insurance companies, telcos – that type of thing.

Dee: You gave a speech where you were talking about The New York Times, which wouldn’t traditionally have adopted tech practices maybe, but you said that they have started to see themselves as a tech company.

Jeff: Yes, and that’s absolutely critical to their success, because they were getting crushed by digitally native news organizations like BuzzFeed and Huffington Post and so forth. And you know, they couldn’t fathom it: “How could we be getting crushed by cat videos when we’re the best journalists in the world?” When they finally recognized that they have to think of themselves as a digital company that delivers great journalism, it fundamentally changed how they work. They still do the journalism they were doing before, but the delivery channels are more diverse. The cadences are different. The reliance on the old print aspect of it has gone down tremendously. And most importantly, they’re changing their cadences of work. They’re realizing that not only do we have a 24-hour news cycle, but we’ve got a 24-hour consumption cycle. We’ve got people who are consuming news all the time, and we can serve them better if we learned how to do that.

“I hear this a lot, especially in large companies today. They say: ‘We miss the old days when we were smaller. We miss the startup days when we could just make decisions more quickly, and we could react in a more nimble fashion’”

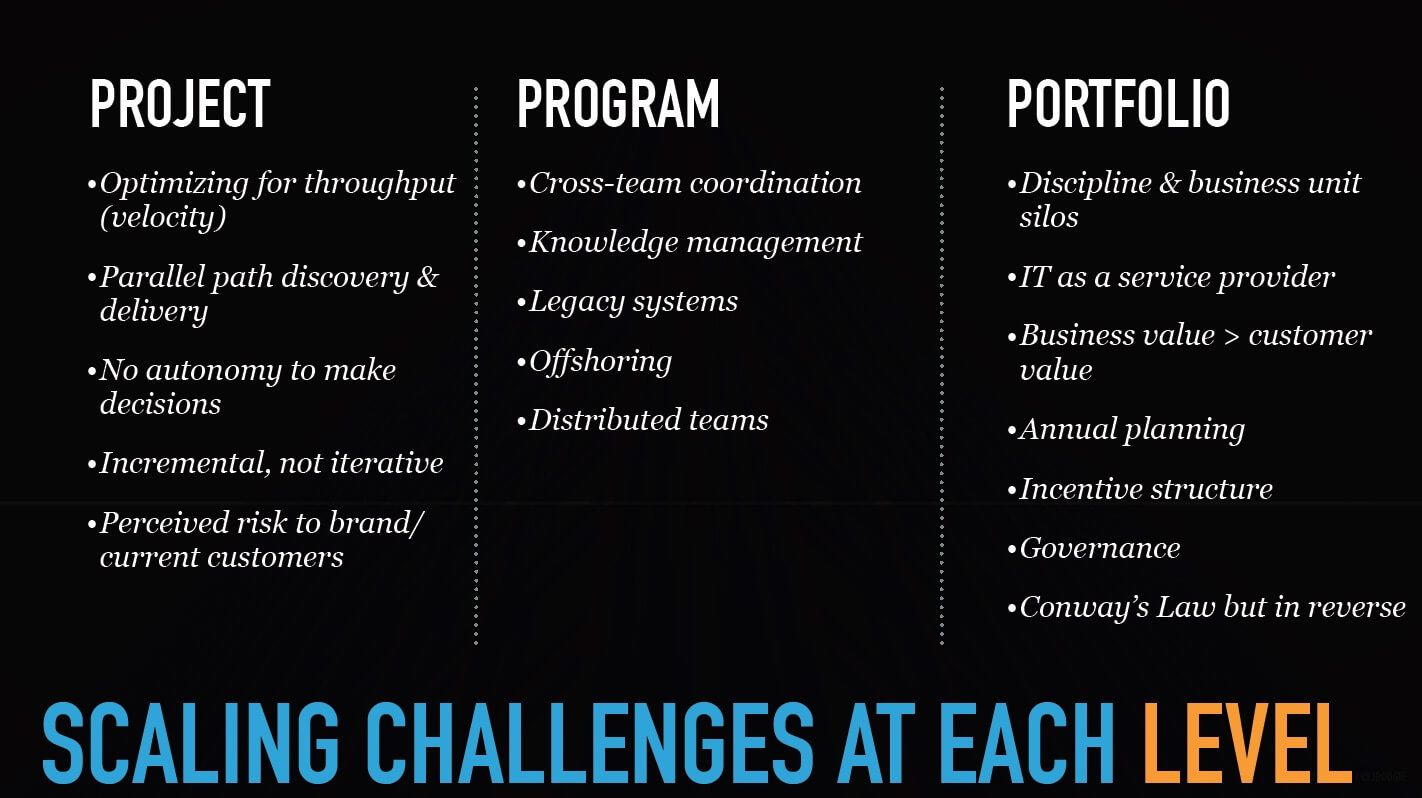

Dee: What kind of challenges are you seeing product and design teams come up against as that business starts to grow?

Jeff: There are a lot of challenges here, but it’s funny: I worked in a high-growth startup for four years about a decade ago. I joined at about the 200-person mark, and it got up to about 400 or 450 when I left the company. What was interesting is that as the company continued to grow, the sentiment seemed to increase. I hear this a lot, especially in large companies today. They say: “We miss the old days when we were smaller. We miss the startup days when we could just make decisions more quickly, and we could react in a more nimble fashion. It didn’t take seven different signatures to get anything done. Twelve people didn’t have to look at everything.” I hear that a lot. As these companies scale, there seems to be a challenge for them in maintaining the pace and the agility they had when they were smaller.

Examples of scaling challenges from Jeff Gothelf’s talk on Scaling Lean

Dee: What can people do before they reach that point to kind of future-proof themselves against it?

Jeff: I was talking to a founder yesterday who’s running an 80-person company, and 20 of those people are in product development. He was asking me very similar questions, and he said: “Look, I want to make sure we do really great product development because I want to plant those seeds now. As we scale to 200, 400, 500, 1,000 people, I want those seeds to flourish so that we understand how we do work, what we value and how we measure success.” I found that to be extremely inspirational in the sense that you don’t hear a lot of founders saying that.

Founders are generally very, very confident about their view and how things should be. Because they have to carry people with them in this belief. But to that end, this particular individual said: “Look, I know my business. I know my customers. But you know what? Digital product development isn’t my strength. And so I really want to work to build those seeds now.” I think that if you find yourself in a similar position – even if you’ve got a hundred-person product development organization, which is still small by the standards of massive companies – you’ve got a real opportunity to build in the reward structures and the kind of culture that values autonomy, that values customer centricity, that values agility and that values evidence-based decision-making and creates the safe space for those things to happen.

Deep empathy for the customer

Dee: If you’re trying to watch out for new competitors or break into new markets, what would be your advice for teams to retain that balance of being responsive but not being overly reactive or unfocused in their response?

Jeff: One of the things that I recommend to pretty much every team I work with – because I have yet to come across a team that’s doing this to the best of their abilities – is that they’ve always got to be locked on to what their customers are looking for, what they’re doing, what their needs are and how they’re evolving. This is particularly interesting if you’re trying to move into a new market or an adjacent market and so forth. How well do you know that market? How well do you know the customers in your market or in the adjacent market? What kind of practices do you have in place to make sure that you are deeply empathetic with that customer and that you continue to do that?

Because the pace of change today is so fast, and the consumption patterns we saw a year or two years ago are simply not the same today. And that’s going to continue to change quickly.

Just because you understood your customer when you started the company doesn’t necessarily mean that those needs and those pain points are the same today – or that you’re meeting those needs in the same powerful way you may have been doing a year ago. So the thing you really have to focus on is how well you know your customer and how quickly you can continue to learn about their evolving needs.

“Just because you understood your customer when you started the company doesn’t necessarily mean that those needs and those pain points are the same today”

Dee: That makes a lot of sense. To move away from the processes side of things: you’ve had this amazing background in design, and I’d love to hear how you think design teams in particular should be adjusting.

Jeff: This is really interesting because I spent 10 years as a designer in the trenches, and then several years leading design teams as the world was transitioning into agile ways of working. It was not an easy transition, and it continues to be difficult because what we’re asking designers to do, and what we’ve been asking them to do for the last decade-plus, is to open up the design process. I’m going to say it’s not a golden age of products necessarily, but it was the golden age of process for designers when we were all doing waterfall. And I’ll tell you why: it was because we had the design phase. Sometimes it was three months, and sometimes it was three days. But regardless of how long it was, it was ours, right?

It was this black box where requirements would come in on one end, and then beautiful stuff would come out the other end. And whatever happened in the middle was our world, and we got to do whatever we wanted in that. That has had to go away in order to build the agility-driven organizations that we’re working in today. We just have to open up the design process and involve people who were traditionally non-designers in that process and to show work much more quickly than we ever would have in the past. That continues to prove to be a challenge for a lot of designers, but it has always been the biggest pushback to integrating design well into these agile processes.

“We just have to open up the design process and involve people who were traditionally non-designers in that process and to show work much more quickly than we ever would have in the past”

Dee: Do you think there is an element of designers not wanting to share the ownership, then?

Jeff: Absolutely. Look, if I’m the designer, and I bring in a product manager and an engineer into a meeting, and we’re discussing design, and we’re co-designing stuff, then what do I do? I thought this was my job. Don’t they write code and manage products? So there’s a value there. There is a shift in the perception of the value that you bring to the organization. Your job as a designer has to evolve to fit into this new world. You’re not just a person who moves the pixels around into an order that looks good and meets the needs of the user and makes sense to them. You are also a facilitator. You’re the voice of the customer. You are the link between the business engineering and product management. There is a much broader set of components to being a successful designer in 2019 than there were in 2009 or 1999 for that matter.

Dee: And do you think because of that historical approach, that as companies grow, design gets a little bit more neglected?

Jeff: I’ve never heard of an organization that said: “Oh we have plenty of designers. We don’t need anymore.” It seems to always be a challenge to get enough designers on staff, and there’s no shortage of open design positions. If you look on LinkedIn for “UX designer” or “interaction designer,” there are thousands of positions currently open. On one hand, I’m seeing design being neglected and not being hired and not being staffed and not being brought on. On the other hand, there are thousands of open jobs as well. So it’s a really interesting conundrum here of who’s hiring, whom they are hiring and why there is a lack of designers in certain organizations, even though there don’t seem to be a lack of job recs for them. It’s this weird mix that I haven’t really reconciled yet, but the one thing that is obvious to everybody is that they can’t not have design at all. Now, how much design they have? It varies from organization to organization.

Establishing design DNA

Dee: One thing you mentioned earlier this week is that a lot of companies don’t have design in their DNA, and that’s a problem. I find that a really interesting statement.

Jeff: Look, if the founders of an organization are not designers and don’t come from a background where well-designed products played a key role in their life and influenced them and that kind of thing, then oftentimes it’s one of the last things to get brought on to a team, certainly in a startup situation. That is an issue when you do start to bring on designers, because they will clash with the culture of the organization. And if they’re clashing with the culture, they’re not going to stick around for very long. So the question is, “If you don’t have design DNA in the organization today, how do you get it?” One way to get it is to bring in a design leader – somebody who is not only a talented designer themselves, but can influence the organization by showing the value design brings and can start to affect the way the company works – to inject design practices into that cadence and then ultimately prove the value of it. You can talk about it all day long; you can show pretty pictures; you can talk about Apple and Netflix and Nest and all these examples of great design. But at the end of the day, if I can’t prove to you that my colleagues add value to our customers and to our company, you’re never going to get behind it.

“People say innovation is everyone’s job, right? I actually disagree with that”

Dee: Do you think that by doing that, designers can actually lead or teach a culture of innovation within the organization?

Jeff: Absolutely. Once a designer has collected enough experience and has worked on enough projects, they are well-suited for beginning this facilitation role that draws in product managers, draws in engineers, draws in founders and business leaders and draws in other designers and builds an innovation practice around them that solves meaningful customer problems. And I’ve seen designers lead those roles. I see that happen more and more in larger organizations, because design leaders end up finding themselves with a seat at the table and an opportunity to access a broad spectrum of individuals inside these organizations. And that gives them the authority and the credibility to then say, “Look, I’ve identified this customer problem, and if you give me four people, we can work together as this kind of small in-house startup team and start to innovate around this challenge, and we can prove to you that it’s going to work.” I’ve seen that work tremendously well.

Dee: If you can actually do that successfully, then do you think that that helps when the company reaches the scaling phase?

Jeff: On the one hand, people say innovation is everyone’s job, right? I actually disagree with that. I don’t think innovation is everyone’s job in an organization. I think incremental improvements should be somebody’s job at the company. Look, innovation means that you are going to try to find ways to disrupt the way you currently do business.

Dee: I suppose if everyone’s disrupting it, then it gets a bit busy.

Jeff: Right. Who’s actually maintaining the system? So we’ve got task-specific teams with the mandate of innovation, and then we’ve got to build those teams and make sure that they include designers on them. That’s it. But it specifically has to be somebody’s job, not everybody’s job.

“Without somebody who understands the customer – who knows how to design these experiences and who knows how to prototype these things – that process is always going to fail”

Dee: If you’re a company that doesn’t actually have design in your DNA, how can you make up ground on something like that?

Jeff: When you spoke with Josh Seiden, he talked to you about outcomes over outputs. To summarize: instead of targeting the delivery of the software as the measure of success, we target change in the behavior of our customers as the measure of success. That’s the difference. If an organization has gone too far down a particular path where design is continuously left out of the conversation – if they start to manage their work to outcomes – they cannot succeed if they don’t incorporate designers into that process. Here’s why: if I tell you to build an iPhone app, you can go build the app. Now, it could be well-designed, or it could be poorly designed, but you built the app, and that was the measure of success. We shipped it. If I say to you, “I want you to increase mobile commerce by 15%,” all of a sudden, you and the team now have to go discover the best combination of code, design, requirements, features, value proposition, pricing model, et cetera, to help make that happen. And without somebody who understands the customer – who knows how to design these experiences and who knows how to prototype these things – that process is always going to fail. If you’ve gone too far, and if the organization can switch to managing the outcomes, it starts to force the conversation around design, which ultimately gets those folks hired and on the team.

Lessons from the human cannonball

Dee: There’s one story from your past about how you worked in a circus, and I was really, really struck by it. I won’t ruin it, because I would love you to tell it for the audience, but I wonder if when a company is scaling, is there some sort of analogy to be made about a growing company?

Jeff: I’ll tell the story, then I can definitely tie it back, because there’s a reason why I tell the story, not just because it’s cool or interesting. My first job out of university was with a circus. I was the sound and lighting technician for the Clyde Beatty Cole Bros. Circus, which was a three-ring tented circus. It was a very traditional kind of circus that went up and down the east coast of America for about nine months. I spent six months on the road, and I met a lot of interesting people. One of the most interesting people I met during that time was the human cannonball. Now, this guy was the picture of what in the US we call “all-American”: football player, blonde hair, blue eyes, fit. And his job was literally to fly out of a cannon during a two-minute act in every show. We did two shows every day, so he worked four minutes a day and landed in a net on the other side of the tent. That was the act.

Now, this was 20 years ago, and it was a fairly mechanical process. There was no digital technology here. It was a spring instead of a real cannon, obviously. Basically, he’d slide down the barrel of the cannon, and the ringmaster would hit a button, and the spring would trigger, and it would push him out, and he would fly across and land in the net. Now, the way they would determine where to put up the net is that they had a mannequin that weighed about the same as the guy. We’d pull up to a new place, and they’d put up the tent, drive the cannon truck in, park it, aim the cannon, put the mannequin in, fire it, and wherever it landed, that’s where they put up the net.

“How critically we’re going to fail depends on how big of an assumption we have. In the circus story, we had a fairly big assumption that this guy was going to land safely in the net, because he had done that continuously for years”

Dee: It’s just not the most exact science.

Jeff: Yeah. But that worked every night of the week for years, right? And then one night, the cannon truck was late arriving to the circus lot, and instead of testing out the location that night, they were going to do it in the morning. They left the mannequin out overnight, and it rained. The next day, they did exactly the same thing they had done night after night for years. They put the mannequin in, they fired it, and wherever it landed, they put the net up.

And that afternoon in front of 4,000 children, the human cannonball got in and waved goodbye. When the cannon fired him, he was significantly lighter than the mannequin, and he flew way past the net in front of all these children. He did not die, but he was critically injured. And it’s a sad story, but at least he lived to tell it in the end. So why do I tell the story? Obviously because it’s interesting, and not a lot of people have circus stories.

Dee: No. I’d wager it’s the first time circuses have been mentioned in this podcast. I’m going to have to go back and check.

Jeff: But look, the story here is about assumptions, right? The connection here is about assumptions. We make a series of assumptions, and they hold true for a while and we stop testing them. We stop ensuring that they’re true. We stop validating them. At one point or another, they’re going to stop being true. And when they stop being true, the thing we’re doing is going to fail. How critically we’re going to fail depends on how big of an assumption we have. In the circus story, we had a fairly big assumption that this guy was going to land safely in the net, because he had done that continuously for years. If you’re building your business, and you begin to scale, and you make the assumptions that even though you’re getting bigger and getting more customers, everything is going to continue to be the same. At some point, that’s going to break, and it’s going to be critical to the success of your culture, your organization, and your business.

Jeff: So it’s important to continuously test those assumptions. There’s a phrase I love – I learned it from a TED Talk by a guy named Astro Teller, which is a great name. He runs Google X, the moonshot laboratory. In his talk he uses a phrase called “enthusiastic skepticism”. You have to run your business with enthusiastic skepticism. It’s this burning feeling that you can always be doing something better. There’s always something that you should be improving, and you’re excited and enthusiastic to find out what that is and how to make things better. That’s the key to all of this.

Sense and Respond Press

Dee: I like that. Just before we finish up, Jeff, there’s one more thing I wanted to ask you. Obviously we release books ourselves at Intercom, and I understand that you run a publishing press yourself called Sense & Respond Press. Do you want to tell us a little bit about that?

Jeff: Absolutely. We mentioned Josh Seiden before. Josh is my long time co-author, business partner, and friend. We run Sense and Respond Press, which is a business book publishing press that publishes short, practical business books for busy executives. The books are never more than 12,000 words long. That’s about 45 minutes of reading, maybe an hour. They focus on business agility, digital transformation, product management and design.

Sampling of books published by Sense and Respond Press

I love this press, because we are helping people unlock their first book, and more and more, we’re using it as a platform to help underrepresented minorities get their first publication out into the world. And we’re super psyched about that. We’ve got 10 books published, which you can find at senseandrespondpress.com. We’ve got seven more books in the works, and we’re always looking for more authors, so take a look at the site. If there’s something you think you’d like to write about, give us a shout.

Dee: So people can just pitch you directly through the site?

Jeff: Absolutely. We’d love to hear from everybody on there.

Dee: Beyond Sense & Respond Press, where can people keep up with your work?

Jeff: I’ve consolidated everything under my own website again for the first time in years. I’m really excited about it. JeffGothelf.com is where you go for blog posts, events, links, whatever. It’s all there.

Dee: That’s brilliant. Thanks a million, Jeff. It’s been an absolute delight chatting to you.

Jeff: Thank you, Dee. This was a blast.