The appliance of science: Mark Roberge’s formula for scaling

It’s the moment every startup must face on its go-to-market path: when to scale and how fast to go.

What kind of information drives that decision: is it subjective and qualitative, or objective and quantifiable? It’s the classic conflict: left brain versus right brain; art versus science. Mark Roberge knows which he prefers. As an engineer by training, in pressure situations he tends to “lean to the quant.” It’s an approach that’s served him well along the road to building the HubSpot sales team, where he was CRO for nine years. That experience led to his bestselling book, The Sales Acceleration Formula.

Applying data and science to scaling has become easier because of the shift that’s happened in the software industry over the past 15 years, from outside sales to inside sales. This has created large amounts of data for running teams.

Yet in Mark’s experience working with and mentoring startups, he’s found that many entrepreneurs go with intuition over information. Or, even if they’re leaning towards the latter, they’re often not using the right metrics. It’s causing them to overlook commonly occurring risks facing early-stage ventures. Those risks can be fatal: Mark has found a 75% failure rate for both Series A and Series C startups (as he presented during his 2019 SaaStr talk.)

Now, as a senior lecturer at Harvard Business School and a VC with Stage 2 Capital, Mark is leaning to the quant once more, identifying a more data-driven perspective on the questions of when to scale and how fast.

Intercom’s Kate O’Hanlon recently caught up with Mark to talk about his approach to scaling, and why it’s a mistake to think that the formula for success is just about getting product-market fit and then adding sales reps.

Listen to the full episode above or check out Mark’s key takeaways below.

A data-driven framework for scaling

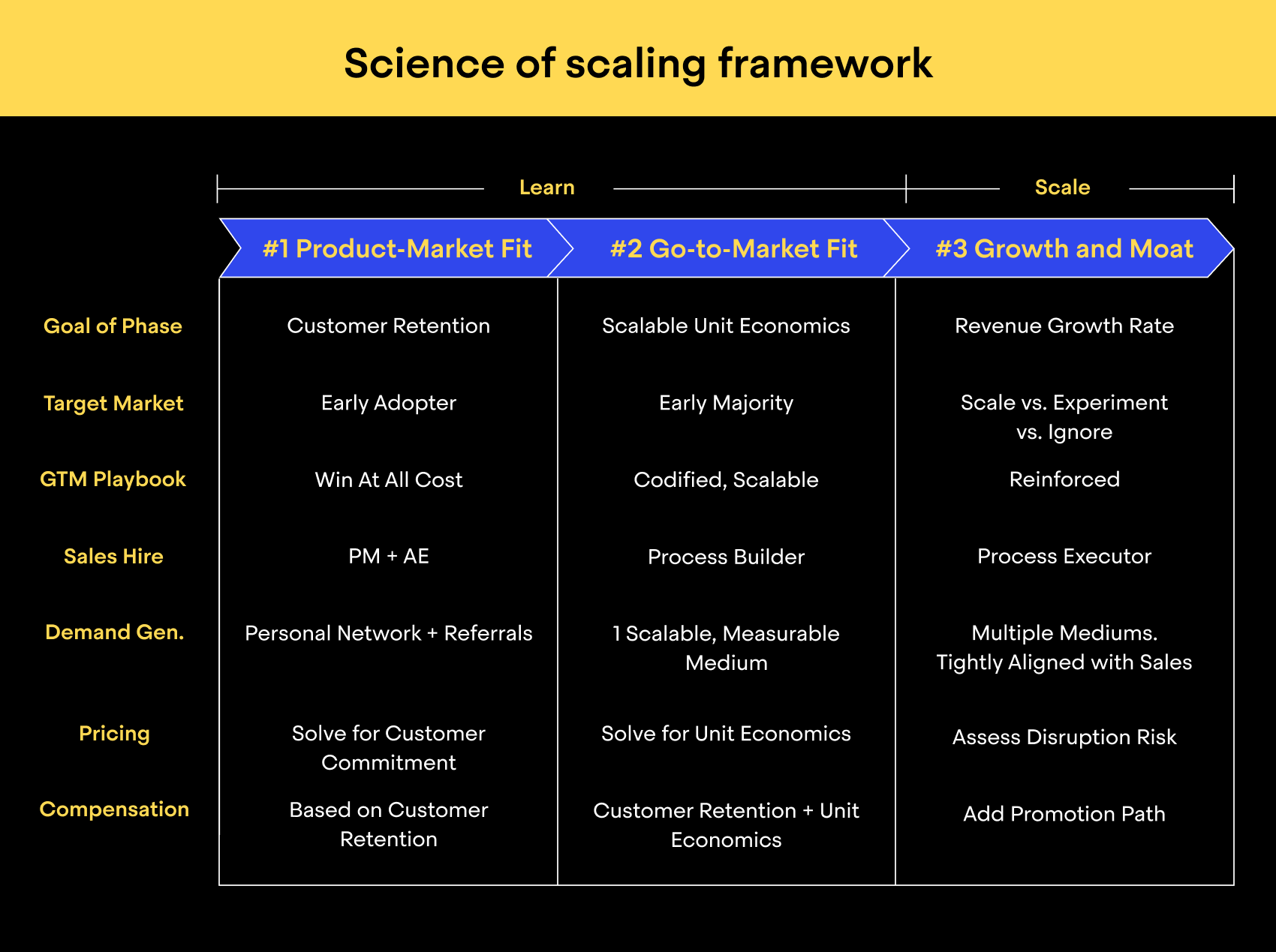

Mark’s latest ebook, The Science of Scaling, outlines a precise framework for success. This approach has been the bedrock of Stage 2 Capital’s method in guiding entrepreneurs and new companies through the scaling process.

The framework consists of three elements: product-market fit, go-to-market fit, and growth and moat. Mark believes product-market fit by itself isn’t enough because it’s too subjective. Even today, when he asks students to define it, he hears a variety of answers like “when I hit a million in revenue, I have product-market fit.”

Mark couldn’t disagree more:

“I just don’t think sales have anything to do with product-market fit. I think that’s message-market fit. I mean, you told the buyer a story, and they gave you some money. Fine. This has nothing to do whether your product solves the problem or not, or whether they still have value. So I think that’s not a good answer.”

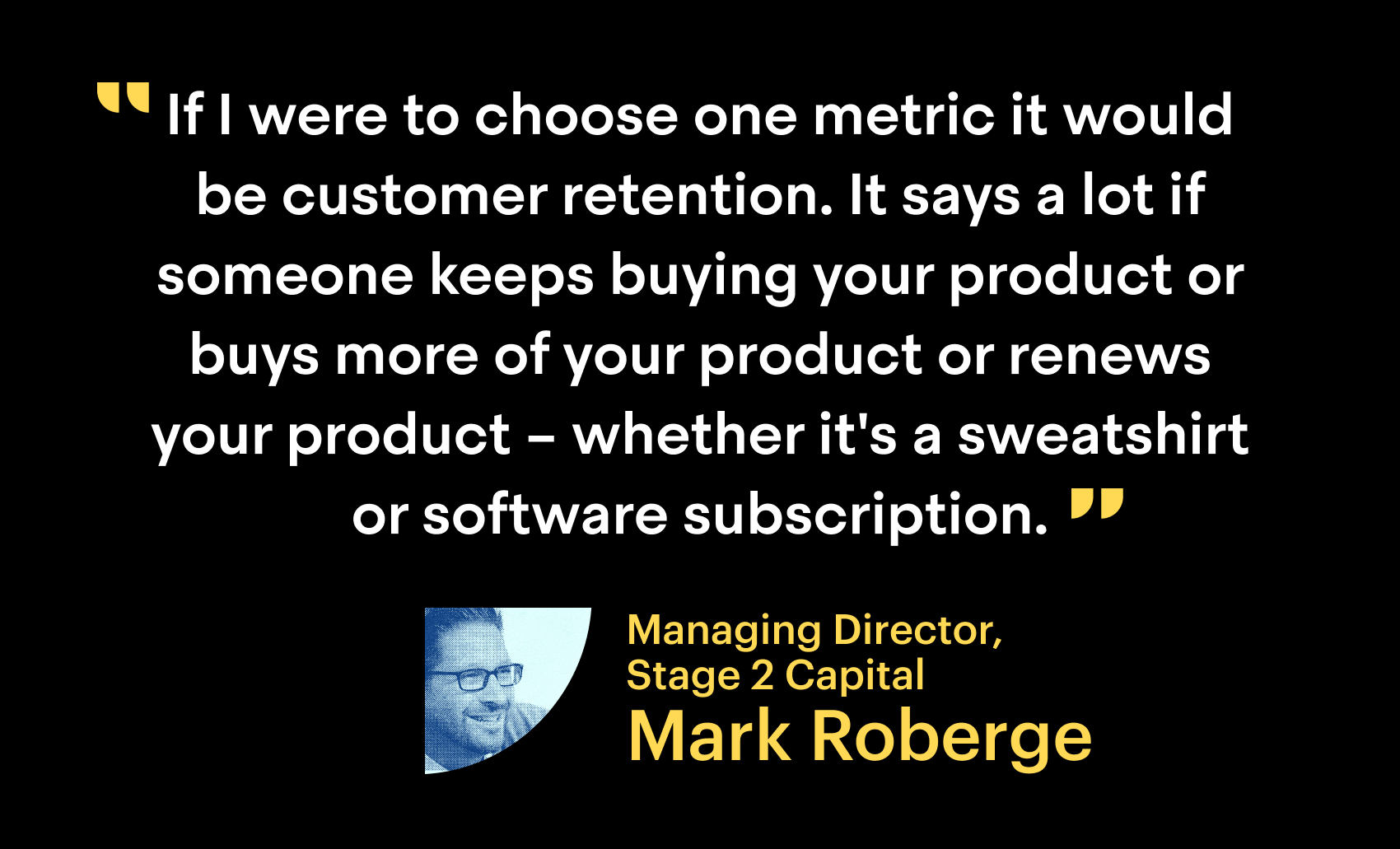

According to Mark, customer retention is a far better indicator of success:

How to spot the leading indicators for customer renewal

By definition, customer retention takes a long time for software companies to figure out, because it might take up to a year to know whether a customer will renew or not. So this leads to Mark seeking out leading indicators. These clues will be unique to each business, but Mark has identified a common formala that has three variables: P (percent of customers) do E (events) within T (time).

For example, Slack might measure this as 75% of customers sending 2,000 team messages within 30 days, or for Dropbox it could be 85% of customers backing up their files within one hour. Recalling his own experience at HubSpot, Mark says the leading indicators were 80% of customers using five or more features out of 25 features within 60 days: “I think that’s a much better approach than a big, workable product in a big market.”

As a general rule, Mark has found the P percent usually falls between 60 and 80, and the T is usually 30 to 60 days. The E is hard to define, and is usually linked to product setup or usage, or if you have a low time and effort to value, it could be seeing some sort of value, like a lift in leads, or a similarly measurable element.

But before everyone reaches for scale, Mark urges caution:

“At the product-market fit stage, all that’s happened is we’ve proven that we’ve signed up a handful of customers – whether that’s 10, 20, 30 – a large percentage of them will see the value that we promised them. We’re creating that value consistently. That has nothing to do with profitability and scalability. In fact, I’d encourage you not to do scale. I’d encourage you to do unscalable things at that stage.”

As an example, Mark refers to his friend, David Cancel, who founded Drift – in its early days he personally flew to onboard customers that were paying $50 a month. Mark says:

“If you’re doing that, that’s good, during the product-market fit stage. It is so hard to invent the business idea one day, and to literally get 80% of your people you sell to to realize the value. If you do that, you have achieved something that so few entrepreneurs have achieved. And you should just throw everything and the kitchen sink at them to make that happen.”

When to optimize for scalability

Next comes go-to-market fit. In the world of SaaS, this is usually in the form of unit economics: a customer lifetime value (LTV) to customer acquisition cost (CAC) ratio of greater than three, and a payback period of 12 months or less. Instead of looking for lagging indicators where you won’t know until months later whether the effort was profitable or not, go-to market fit is a leading indicator for unit economics. Mark says:

“Knowing that we want to have an LTV to CAC ratio greater than three, we just have to calculate what that means for our sales activities today: how many appointments a week do our SDRs need to set up? What does the conversion rate from appointment to customer need to be for our sales reps? What is the average sales price for the customers that we sell?”

These are some of the inputs that businesses can put into a revenue cycle management (RCM) dashboard to understand if it’s scaling profitably.

Mark says that while having scalable demand isn’t important at the product-market fit stage, it’s essential for pursuing go-to-market fit:

Aligning teams around customer needs

The final stage is growth and moat – this is where a business can start to add sales people. But how fast should companies hire? Mark advocates letting the numbers dictate instead of a mass recruitment drive. Having instrumented leading indicators of customer retention and unit economics, it’s a matter of watching what Mark calls “the speedometer.” He says:

“Our work in the product-market and the go-to-market phase of finding our lead indicator to customer retention, our lead indicator of unit economics, becomes our ‘speedometer’ as to how fast we can actually scale.”

The growth and moat stage is where the management layer happens. And the teams now need a more defined structure. Mark says some of the large consultancies have partners who can network, make the appointments, close deals, and lead the delivery. “That’s the optimal design,” he says. It’s good for the customer and cuts out a lot of alignment complexities for the manager.

Yet the trend in most SaaS businesses has been to have specialists: one to set the appointment, another to onboard the customer, and another to expand. There are lots of advantages to this – not least because it means companies can hire for specific skill sets. But you want to avoid having a large business development rep (BDR) team setting appointments for a big account executive team, for example. Instead, Mark advocates grouping teams by customer type or geography.

This creates stronger alignments within teams and avoids the risk of setting up bad meetings that don’t lead to sales. More importantly, it builds empathy that leads to stronger working relationships among the team.

You can also read a full transcript of the interview which has been lightly edited for clarity.