What we learned about product and design in 2018

As we've done in past years, I sat down with Paul Adams (VP of Product) and Emmet Connolly (Director of Product Design) to reflect on the things we've learned in the last 12 months.

Our conversation comes from the value we have at Intercom to continuously share the lessons we’re learning about growing our product and our team.

Short on time? Here are five quick takeaways:

- As our pace of shipping increases, it’s important to take the time to understand the difference between output and outcome. Are people using the things you shipped?

- As your team grows, invest in operations and design systems that will help you scale efficiently. You’ll know they’re effective if over time you have the absence of things slowing you down.

- Don’t ignore the voice of your unmet customer — the prospective customer who didn’t become a user because of a product shortcoming. We built a process with the Sales team called “Problems To Be Solved” to capture this feedback.

- The best product strategy is one where new features build upon previous launches to provide compounding value for the user. Case in point: our new Messenger, bots and App Store all work together to help businesses connect with their customers in new ways.

- Hiring in the new year? Look for product managers who are open and collaborative instead of godlike. Think about the shape of your team and the gaps that you want to fill. Find people who understand it’s a team sport.

If you enjoy our conversation, check out more episodes of our podcast. You can subscribe on iTunes, stream on Spotify or grab the RSS feed in your player of choice. What follows is a lightly edited transcript of the episode.

Des Traynor: Welcome to the Inside Intercom podcast. I’m joined today by our VP of Product, Mr. Paul Adams.

Paul Adams: Hello. Nice to be here.

Des: And our Director of Product Design, Mr. Emmet Connolly.

Emmet Connolly: Happy 2019, lads.

Des: We’re going to look back on last year, and we’ll talk specifically about running the product org at the scale we’re at today, in the hopes that our listeners can learn something from this. That’s not to say that we have all the answers, but we certainly have a good list of questions at this point. How big is the R&D org today, Paul?

Paul: In total, we are over 200.

Des: And what’s the breakdown there? About how many designers do we have?

Emmet: Seventeen product designers and three content designers.

Des: And then how big is the product org? If you add in all the PMs and all that, how does it break down?

Paul: We have product and engineering – which we call R&D – but it’s a product and engineering org. And product is made up of design, product management, research and content design. It’s about 50 people, and the rest are engineers, basically.

Des: And that covers, of course, not just product engineers, but everyone working on foundations, security, stability, infrastructure – you name it. We grew by nearly 100 people last year, so I’d say that’s a significant lift. Nearly 50% growth. I presume everything worked smoothly.

Paul: Very easy, yeah. Just happened by itself.

Output vs. outcome

Des: In your eyes, have things slowed down at all? What’s worked? What’s broken?

Paul: It’s an interesting question. We’re being more thoughtful about different things, more deliberate. But shipping hasn’t slowed. In fact, I think it’s increased in pace, even when you take in to account all the additional people we have – which is actually something we’re pretty proud of. Intercom has always held near and dear our ability to ship, and the thing that I’ve always kind of reacted against over the years is inefficiency. I think this obsession with efficiency comes from the startup days when being wasteful was a debt.

Des: I remember you were probably – without commenting too much on your former employer – somewhat scarred by previous teams where there was inefficiency or where projects got canned or whatever. Without mentioning specific logos, wouldn’t it begin with an “F” or a “G”?

Paul: Yeah, companies that begin with “G.” Most of my career, pre-Intercom, I worked on things that never shipped. I worked on products for more than a year that were then cancelled. When that happens to you a lot, you get burned, and you’ve deep scars that probably going to remain for life. I’m sure Emmet’s got a few of those from the big “G” days too. So, I think we’ve always had this obsession that has continued to this day, and this year has been really good on that front. We’ve managed to ship a phenomenal amount of things, to our level and quality. We have an obsession with scaling process and efficiency and just being able to have something that people can understand that works.

That’s very customer-centered, which means two things: new people can join the company and slot right in. They know what to do quickly, and so if they’re an engineer, they’re shipping code very fast. It also means things have a very low risk of failing. We think a lot about what we build, and we spend a lot of time on research and problem identification and prioritization, so the things we do end up building are solving problems our customers actually have.

Des: I have to push on this: has it all been one-way traffic? One doesn’t simply grow by nearly 50% and not have a few fuck-ups along the way.

Paul: There are different ways to think about that. Something we’ve talked about internally this year — and a topic that has been talked about externally — is the difference between output and outcome.

“There is often a question: are people using things we shipped? Let’s be honest with that”

We’ve shipped so much this year that I actually don’t know how many things we’ve shipped. I think it’s more than 140 user-facing changes, ranging from the lowest level of making a feature better all the way up to brand new products. And we’ve shipped multiple brand new products this year.

But we have talked about the difference between output and outcome, and certainly if we were to critique ourselves, it hasn’t been all plain sailing. There is often a question: are people using things we shipped? Let’s be honest with that. We have this very important principle here about shipping to learn, not ship and forget. You know, it’s been a challenge to hold ourselves accountable to that because of the pace at which we work.

Investing in operations and design systems

Des: So in theory, 140 features or user-facing changes would mean 140 postmortems and 140 new roadmaps for all these things we’ve just released into the world. Emmet, how has your area of design grown substantially to match all of this? What have been the choke points or the things that worked?

Emmet: As you were talking, Paul, I was thinking about a chat I had recently with a well-respected design team at another company…

Des: Was it Google?

Emmet: It wasn’t Google. I said well-respected. That’s a joke for all my old friends.

Des: Haha, jokes.

Emmet: This person described to me a situation where a team was given huge latitude to invent what they wanted to work on. They would come in and drive their own projects for sixth months, only to have the CEO shit-can it a week before it was ready to launch. What that eventually leads to is a high degree of turnover. Because that really only needs to happen to you a couple of times for you to hit the point where you’ve been in your job a year and not shipped a single thing.

There’s not a lot of flash in our approach. And a lot of the stuff within an environment like that has kind of been operational. We’ve had a lot to focus on quality and product strategy and all that kind of stuff. But really the scaling challenges have been around some of the operational stuff, so we really went quite heavy into design ops, which is a bit of a buzzword, I suppose. But often it’s about taking those buzzwords and asking, “What does this mean for our company at our scale?”

“Things like design ops and design systems are a bit trickier because they are really successful if you have the absence of things slowing you down”

To define design ops, it’s really just a process by which you improve the operations of how you do basic things like design crits and design process and so on. It’s a structure whereby the people and the teams can bubble up the problems they’re hitting on a daily basis. We really treat our process like a product that we iterate on constantly. So we get to use our designer brains, not just to iterate on the product we’re building, but how we do it.

Des: I feel like amongst our listeners, a lot of people are fighting for budget for design ops and being told they don’t know what the hell this is. Can you give me an example of a tangible output from having design ops that people could expect and be rewarded for?

Emmet: So, it’s a tough one. Design systems falls into the same camp in that it’s hard to point directly to a dollar value they create. As you scale, you orient your team toward demonstrating some kind of value for the work you do and justifying where you spend your energy. Things like design ops and design systems are a bit trickier because they are really successful if you have the absence of things slowing you down. It’s still hard to measure, but a signifier of these things starting to work are when you realize that a lot of those annoying project resets we used to have – or those cases where we get far into something and have to ditch a bunch of work – start to go away. A lot of the stress or uncertainty for people who are actually working on projects starts to dissipate as well because they’re just better set up. So, it’s really oriented around quality and speed and the absence of those things not being there.

Des: That makes sense. Paul, do you have a question?

“Operations is actually the thing we’ve always been a little bit obsessed about”

Paul: I was going to add one other thing, and it’s going back to your original question. One big difference is that we now have substantial product and engineering offices in Dublin, where we’ve always been based. But now we’re also in London and in San Francisco. So, we have three. We just made this global team, so Emmet and I and other leaders have to really think about how do we continue to ship and grow and be successful in a world where we have people who are not even in the same time zone as we are. They’re asleep when we’re awake and vice versa. And operations, like design ops, is really cool in 2018 – as is research ops and product management ops, which will be coming next year.

Des: And VP of Product Ops.

Paul: Yeah, can’t wait for that.

When you think about it, operations is actually the thing we’ve always been a little bit obsessed about. You know, program management falls into this category, too. This time last year, we were talking about how program management had really changed Intercom for the better in this regard. And we’ve continued to invest in that too. When it’s properly understood, this whole idea of operations results in a world in which people are way less frustrated with, like Emmet said, things not shipping, course corrections, not knowing who to talk to. Maybe a year ago, people would wonder, “When should I be involved?” Now they don’t.

Des: And you probably don’t show up late in a project and throw it away, because if you needed to be involved, the process would’ve gotten you in at the right time.

Emmet: Exactly.

Des: Emmet, can we go back to design systems for a second? Was this a substantial investment for us in 2018? Help our listeners think about when and how to invest in it.

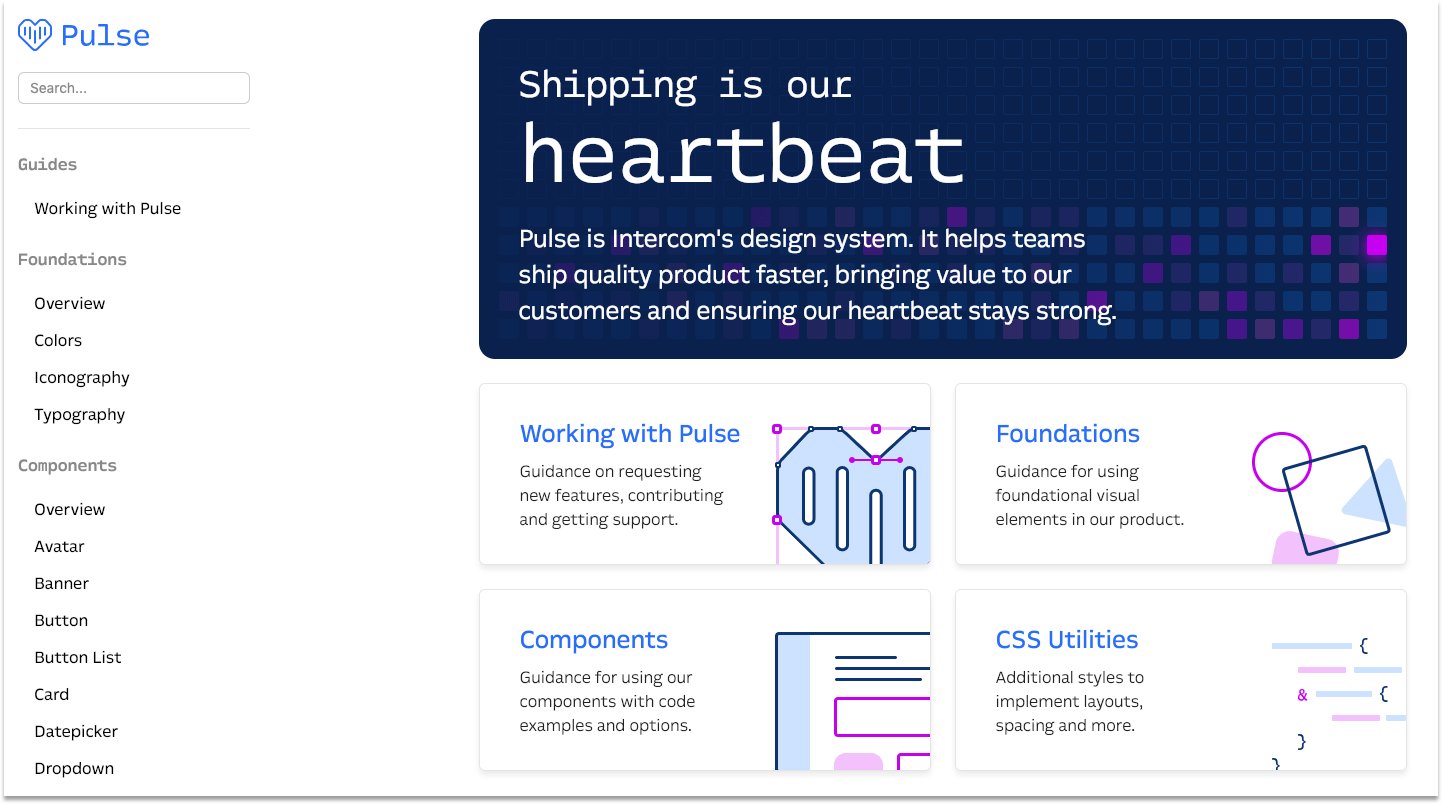

Emmet: Yes, we ramped up investment in it specifically. We had always had basically a skeleton team on this, where we were going from the standard pattern libraries and a set of UI components toward something more robust. To get the more robust thing, which I’ve written about in the past, we think of a full stack design system that touches all points of your product. We now have a design systems team that is basically fully staffed, with two designers, a PM, and an engineering manager and two or three engineers. It’s a substantially staffed team, and that’s a good investment. As to when to get there, I don’t think it’s a quota where you do it before you get to 20 designers; I think it’s more a function of when shit is starting to break.

Des: What’s a problem sign? If you find in your org you’ve got nine different implementations of roughly the same button, but they’re all slightly different – maybe that’s a facetious point, but is there a more general indicator?

“Something that seems like it shouldn’t be a huge investment is difficult because there’s some design debt or technical debt in order to rationalize what’s there already”

Emmet: It’s things like that. I think another warning sign is that you start to hear a loss, and it’s difficult to do simple things right. Something that seems like it shouldn’t be a huge investment is difficult because there’s some design debt or technical debt in order to rationalize what’s there already. So you realize you need to invest a bit more in having the right building blocks so that you can build a product out of them.

Des: You spoke before about the size of those building blocks, as well. Historically, when pattern libraries emerged, they were at the very atomic, component level, like showing how a dropdown looks. But when I look at our pattern library, it’s much more about how we lay out a form or display a user list. They’re big Lego pieces to play with.

Intercom’s design system

Emmet: Yeah, and they’re the big pieces of the Intercom products, like Messages and Articles and customers and things like that. Again, design systems can be kind of a trendy thing. You have to figure out what it means to you and your company. We’re particularly well-suited to make the most of it, given that what we’re building is a suite of products. If you have a large software footprint and you built them all somewhat independently, you’d have inconsistent products. That would be a shame. But also, you’d have people building the same things or very similar things again and again and so to Paul’s point of shipping 140 things a year, that number is going to drop when a lot of people have to manually build the same thing again and again. For us, it certainly works well. But again, I think you need to figure out what it actually means to your org.

Listening to the unmet customer

Des: Paul, one area where I think I experienced a change in how our product engineering teams work is in our relationship with go-to-market teams – specifically how we deal with some of our larger customers or prospects. One thing that occurred to me very early on when I moved back to R&D (or to Product and Engineering land) was how we have a lot of inputs to our roadmap. But one customer whom it’s fundamentally impossible to listen to is the voice of the customer who couldn’t adopt to your product. I’m talking about someone who ultimately couldn’t agree to buy it because of a shortcoming. Everything else has its way onto the roadmap with the exception of this, right? After multiple conversations with the folks in sales, you took point on this. Talk us through it what we changed there.

“But one customer whom it’s fundamentally impossible to listen to is the voice of the customer who couldn’t adopt to your product”

Paul: Yeah, it’s interesting to try and track the journey over the years, because Intercom’s changed a lot. There are lots of people listening to this, and you have companies of all different types and sizes. And when we were smaller, our self-serve channel was so dominant, at least in how we thought. You know, people just went to our website. They found about us by word of mouth, Twitter, talking to people they know in the industry. They went to our website and signed up themselves, and they were up and running. As we got bigger and bigger, and as people got to know Intercom, we got bigger companies knocking on door with more complex requirements. Often, I used to talk to someone because, as good as any marketing might be, they’re just not going to answer every single question people have. I found that we started to have more and more companies who just wanted to talk to us about Intercom. So our sales team kind of grew out of that, and it’s been really successful.

And as you said, there was definitely a lag between the sales team growing inside Intercom, and us in product engineering actually realizing that we needed to listen. You know, we’re very open. It wasn’t like it was a deliberate thing. It was just more that we were a little lagging. The hard lesson I learned was: “Oh, shit. There’s a whole critical input here that we’re just missing.” And so we changed that. But you know what we didn’t do, very explicitly, was whatever the respective customers were asking us for. That’s obviously not a good path; it’s a path to ruin over some period of time. If you just start building one-off features and changes, that just make your product a big mess. So like we’ve always done with operations and process, we sat down with the sales team over the course of weeks and months and together, very collaboratively, built a process. We iterated it over the year, gathered all the inputs we were hearing, synthesized them and pulled out the patterns.

“We directed the sales team to have the customers think in terms of the problems that they had”

One big change was that customers typically ask for very specific features. But we directed the sales team to have the customers think in terms of the problems that they had. It was kind of like a classic design thing; if you’re in the world of design, it’s a very common way to think so that you ensure you understand peoples’ problems and figure out the best solution. But you know, if you live in the sales world, that’s not common. So, it was awesome. We built this process together called “Problems To Be Solved,” which is very self-explanatory.

Des: Borrowing from Jobs To Be Done.

Paul: Exactly, yeah. It’s got an acronym too: PTBS. It’s literally a list of prioritized problems to be solved. And it’s taken from hundreds and hundreds of weekly and monthly sales conversations to create a new input around making Intercom better based on the things that prospective customers are looking for.

Des: And obviously they have to be traded off against the current customers, the things we have, the ideas we want to build and all the new shit we have to do in a given year. It’s been quite a force of maturing for us, I’d say, to bring in the sort of voice of the unmet customer.

Paul: Very much so, yeah.

Emmet: It’s just one of those things that’s a no-brainer in retrospect, as well. It’s something of a truism among designer/product people to “know your user.” Nobody talks about knowing your prospective user: the person who isn’t a user because you have already failed them.

“Nobody talks about knowing your prospective user: the person who isn’t a user because you have already failed them”

Des: I think that’s exactly it, especially where it’s a blocker. These aren’t people saying, “I’d use you if only you’d also add five more features so I could do face ID tracking.” It’s always, “I want to use you exactly the way you intend to be used, but I just need this extra piece of permissions or security or settings to actually unblock me and my team from adopting.” They want you to unlock an extra piece so they can adopt a tool that meets their standards and criteria.

Emmet: Then I roll in and ask whether it’s something that makes sense for the product holistically, rather than just responding to those sales blockers.

A product strategy that creates compounding value

Des: Absolutely. Speaking of new shit we wanted to build, last year, we rolled out Messenger 4, which is a whole new messenger, a new home screen, new design, new launches, new everything. We launched an App Store, where apps could exist inside the Messenger. We launched a public version of the Intercom App Store, where now you can actually search for these things on the web and find them. We launched Custom Bots, which was basically a way to start conversations and put a user down a certain bot-driven path. Then we launched Answer Bot (now called Resolution Bot), which is a way to understand and infer and automatically answer customers’ questions.

None of those things were requests from our sales team, nor were they requests from our current customers. All of them were net new things we wanted to do at the start of the year. But I remember a tweet you had out ages ago, Paul, where you said that strategies that reveal themselves in hindsight are your favorite type of strategy.

I’ve always admired product strategies made up of launches that build on each other, each one making the prior ones better – creating compounding value for customers. Today @intercom we launched part 3 of such a strategy:

— Paul Adams (@Padday) August 8, 2018

Was this one of those things where you had all the key components in your mind’s eye at the start of the year? Or was more of a we’ll-ship-and-learn-and-adapt approach?

Paul: Yeah, it’s a great question. It’s definitely both. I think it’s more the former, that there was a plan. Now that you asked the question, and we were kind of joking about the Google and Facebook days earlier, it does remind me of that time in my career – which is going back a long time now and those companies have radically changed since then – when I was at Google, working on social products, and Facebook was this company three miles away that was a big, giant mystery. And every time Facebook launched something, it was individually impressive. And then you’d wait and see something else a month later. They were very fast at shipping back then. Significant new things would start adding up and adding up, and it blew my mind.

It was a real career moment – an eye-opener for me, because I was still learning what strategy even was. And I was like: “Wow, the sum is greater than the parts, and these are all connected, and they’re unlocking. There’s literally a path of unlocking here. Someone had a plan; this isn’t an accident.” Every time Facebook announced another new thing that built on the prior ones, it was way harder for Google to compete. They were building up defensive moat after defensive moat. And it’s never left me since then: the idea that you should design these ecosystems that are connected, where the sum is greater than the parts. For us this year, that was definitely playing out. As we said earlier, we also have this value of shipping to learn. So there’s some humility on our part, knowing we have this value and being confident and humble in one ship. We should be confident in our decisions because we run a good process and yet humble in the fact that we don’t know everything.

“It’s never left me since then: the idea that you should design these ecosystems that are connected, where the sum is greater than the parts”

Des: If I had to put on my entry-level PM hat, I’d probably cry and chuck my toys out of the pram and say it sounds like you’re trying to plan a roadmap upfront. That sounds crazy. Is that what happened?

Paul: That’s called strategy.

Des: But is that what happened, where you said, “Hey, there are big components here, and all of these are happening unless we get significant alternative feedback from the market”?

Paul: Yeah, pretty much. Toward the end of the year we had an event called The Next Chapter, and our co-founder and CEO Eoghan got on stage and talked about our Messenger (which has always been core tenant of Intercom) and bots and apps. And so, what we did this year was effectively play out that vision and strategy piece by piece. And actually, it’s still early days. We have so much more coming that will build on this.

But it was the case that the new Messenger had this thing called a home screen. And on this home screen, you could embed apps within the Messenger.

But where are the apps coming from? We realized we need to have people build them, build some ourselves and have an App Store. The more we grow the App Store, the more we’ll learn from people using the apps or not using the apps. We’ll iterate. So the apps will get better and better, and therefore the Messenger gets better and better. Then you’ve got bots, and bots can live in Messenger conversations. Bots can deliver apps. An app could pay a bill, or start a video call or whatever. And the more apps there are, the more the bots can deliver the apps. All these things just make each of the others better and better. So we did actually play that out, and we also launched Messenger 4 with no beta, which was risky, and so on.

Des: Yeah, that was scary for that exact reason: simply telling 30,000 people their favorite Messenger is changing is always risky. Emmet, from a designer point of view, when Paul does this strategic roadmapping of the year without telling anyone, how do you equip the designers to not have to redesign after we release new things? Because if there is some sort of grand plan, then ideally you’d design with one eye on the bigger picture the whole time, right?

Emmet: Well, it’s a fairly collaborative process to come up with this at the beginning, so it’s less an idea of taking the stone tablets down from Paul’s office and presenting them to the company. People are voting because they’re involved and feeding into this stuff from the start. The other thing is that the one-minute overview Paul gave was probably the extent of detail we had at the beginning. So a lot of what Custom Bots would actually look like and how the apps would work was completely unknown. Another advantage of doing this in individual parts that add up to something greater is, you get a greater sense of stability. By the time you’re building that fourth piece of the puzzle, you already have the first three pieces, so you’ve got way more clarity on what a good solution is going to look like. By the time we got to Custom Bots, we already had the home screen in the new Messenger; we had the Intercom App Store; a lot of the constituent parts were vetted down; and so it’s a kind of a narrowing-in process over the course of the year.

Hiring product managers and design leaders

Des: Paul, you mentioned earlier the need to be confident yet humble. I suppose you mean being assertive and deliberate in what we’re trying to do, but humble enough to realize you might get it wrong, or you might not know the answer about certain things. I know you’ve said before that that’s one of the most important traits in the PM world. For whatever reason over the past five years, PMs have – I’ll say it so you don’t have to – adopted maybe a type of god complex in a sense, where they think they’re the center, and they’re kind of expected to know everything up front. When you’re interviewing for PMs these days, what’s the trait you look for? How do you test for humility and yet at the same time make sure there’s enough confidence there?

“They get the best results through a collaboration, not through a single-minded vision”

Paul: It’s a pretty big question. I’ll start by talking about product management more broadly. Product management on one level is an old discipline; I think Proctor and Gamble first invented it in the ’40s. In tech these days, it’s obviously a core part of any technology company’s road for product manager. It’s kind of exploded, and so still in some ways, even though it’s old, it’s relatively new. And as a result, it’s not well defined.

You can go from company to company and see people doing wildly different things, some of which looks a lot like project management. They’re actually driving forward a vision or strategy for a product; they don’t own a product. Some of it is just taking orders from someone else who decides what the product is going to be, and they just execute the orders they get, and they’re the product manager. In other companies, they’re expected to be a mini CEO. If you’re a young product manager early in your career, I’d be amazed if you’re able to figure out what you’re supposed to do. There are so many conflicting opinions and views.

We have our view, which is certainly not shared probably by some other companies. But for us, the road to product manager is similar to the bigger tech companies. Google, probably more than any other company, popularized the road of product manager going back maybe 20 years, where they’re a core collaborator with engineering and, increasingly, design. At Intercom it’s always kind of been that way, where the three functions collaborate with the help of content design, research, product analytics, etc. But it was always that kind of trifecta of PM, design and engineering. But depending on the company, each one of those three has different influence, and I think in a lot of companies, the god complex you talk about is because someone anointed the PM and said, “You’re in charge.”

Des: “You’re the tie breaker.”

Paul: Yeah, and “the buck stops with you.” As a result, people then go around with this idea, a kind of inflated sense of being. Whereas, I’ve always found the best product managers absolutely need to have product drive and product taste and product sense. But also, they’re incredibly open and collaborative, and they’re not godlike at all. They get the best results through a collaboration, not through a single-minded vision.

Des: Emmet, you’ve been hiring design leaders for most of last year as well. Obviously all designers have some belief that they are a higher being, let’s say.

Paul: Except for Emmet.

Des: Except for Emmet, who’s Mr. Humble here, sitting in front of me. What are the traits you’ve been looking for in designers and design leaders?

“You need to think about the shape of your team overall and what your gaps are”

Emmet: You can probably imagine it is some kind of hierarchy-of-needs diagram. There’s a lot of the table stakes stuff (like skills or technical ability), so you’re screening for that stuff at the start. I think experience counts for a lot. There’s a lot that is involved in the actual work we do that really you need to learn in some form of real-life scenario. And then beyond that, there’s probably some stuff around aligning with our values as well and someone being an add to our culture rather than just fitting into it and so on. There’s no hard and fast thing, because I think you need to think about the shape of your team overall and what your gaps are. Otherwise, you’re just consistently hiring for the same type of person and you’ll end up with a team that, where everyone shares the same maybe gaps, right, as well as strengths. It might change. A lot of the time, you’re thinking about filling the gaps. You think about the team holistically in terms of seniority, and you don’t want to be too top- or bottom-heavy in terms of experience. And as we scale, specialization is a thing. It’s a blend of the stuff; imagine it’s a pyramid. The stuff at the bottom of the pyramid is fairly stable, and then towards the top…

Des: It can tilt either way.

Emmet: It depends on the situation, where you are as a team and what specifically you’re hiring.

Think you’ve got what Paul and Emmet are looking for? We’re hiring.

The end of navel gazing

Des: Okay, the last question is one that I think both of you will have some familiarity with. Paul, you gave a talk at last year’s UX London called The End of Navel Gazing, where you basically said that some of these roles spend far too long trying to figure out their place in the organization and their proverbial seat at the table. What motivated you to write that talk?

Paul: Oh yeah, it definitely is a big one.

Emmet: It was one huge subtweet aimed at me, I think. Is that it?

Paul: It was actually the biggest subtweet I’ve ever seen.

Emmet: Okay, I’m glad! On stage, in front of hundreds of people.

Paul: It was aimed at anyone who’d listen. It’s definitely applicable outside of UX and design. I actually gave a version of the talk to test out the material a little bit at Mind the Product, which is a PM conference. It came from something that’s been building for years and years inside me: some level of discomfort with the UX industry. We’re feeling disconnected and disempowered, and there’s a lot of complaining on Twitter.

Des: “Why won’t they listen to me, we’re so smart” type of stuff?

Paul: Yeah. People saying: “Where’s my seat at the table, oh, I got a seat at the table, oh, this is a crap table, is there a better table around here, I’m not turning up at the table anymore because I don’t like what you all are saying.” That was the tipping point for me, of feeling like I should just write this talk and make the point heard. The lesson in it all was that the UX industry tends to say that it’s the voice of the user. That’s the kind of stick you get beaten with: “We’re the voice of the customer. How can sales or marketing or the CEO…”

Des: Pretend to know anything about them?

Paul: Yeah, you know, “You’re not the customer, I’m the customer.”

Des: “I spoke with the user, and they presented this wireframe to me.”

Paul: Yeah, and it’s a stick they beat people with. Here’s a timeout from the talk: there’s about 400 or 500 people in the audience, and I ask them to put up their hand if they speak to at least one customer a week. And like three people put up their hands.

Des: That’s the voice of the user.

“We’re one spoke on the wheel, and sales and marketing and everyone else has an equal part to play”

Paul: I said: “Well, guess what? Your sales team talks to 10 customers a day, at least. Your support team talks to 40 people a day. Those other parts of your company are far more representative of the voice of the user than all of you, than all of us – I was in this group, too.” And I told them that we need to wise up and realize it’s a team sport. We’re one spoke on the wheel, and sales and marketing and everyone else has an equal part to play. It’s imperative, for the industry to move forward and mature, that people en masse realize that they are one of 10 or 12 spokes on the wheel, and therefore you’ve got one-tenth or one-twelfth of the influence.

Des: And not to be glib, but the subtweet-ish component of it was something like, “Stop spending so much time debating this with other people in the UX design community about the nuances of a persona, and go talk to your sales team or your support team or your marketing or anyone else who’s closer to the business than you are,” right?

Paul: Exactly. The reason it’s called “The End of Navel Gazing” is because this frustration is born out of a really misunderstood view of one’s place in the world. People tend to just start looking inward: they got the seat at the table, and now they don’t like the seat, so they’re not going to fight to understand what the seat even means. They’re just going to complain and fight over the tools. There’s a big, bad world out there of real people; go start talking to them. Stop pondering internally.

Des: Emmet, this doesn’t apply to all designers, does it?

Emmet: No, not for personal company excluded, anyway. I think designers should have a throne at the table.

No, when you were talking there, I was thinking that design in the broadest sense has a very long history. Have you ever heard the story of when Steve Jobs was at NeXT, and he got Paul Rand to design a logo for him, and Paul Rand was like, “I will do one logo, and you can use it or you can not.” There’s this sense that a designer is a genius who delivers work from on high, and like it or lump it. Designers are special, and you can take the work or you not. That’s just a different job to compare to the type of work that we’re doing, which is so collaborative within a complicated organization that has so many required inputs that no one person could ever handle on their own.

I think the reason that it’s this ongoing point of conversation for some people, perhaps, is that it triggers this existential crisis because they thought they were one thing, and then they do get the opportunity to have the seat at the table. But then what’s being asked of them is completely different to what they thought they were. This is not helped by the fact that you look across the industry at all these other teams, and you see just the outputs they created. You don’t see all the messy stuff that was happening – the rest of the iceberg below the surface that got them there – and so you tend to valorize things like the output into one single delivery, because that’s the reference point you had going in. And maybe that goes back to what I was saying, which is that experience really counts for a lot here. When you get some of those lessons under your belt, you realize: “Wow, I need to do more. It’s more than just headphones on, sitting at my desk, delivering design work.” It’s extremely collaborative.

Des: Okay, I think we best leave it there. Thank you both so much for your time. That was 2018 and running Intercom at the scale we’re at now. Join us next time, when we’ll talk about 2019 and all the new things that are coming.