Reaccelerate: Finding new engines of growth in your business

At this year’s Web Summit conference in Lisbon, I gave a talk on how businesses should think about weathering these tough economic conditions, and indeed how they can actually find growth during them.

You can check out the slides here, or read on for an illustrated transcript of my talk.

Hi, I’m Des from Intercom. I’m going to talk about reacceleration – how to find new areas of growth in your business.

Now, why are we talking about this? I think we’re all going through a moment that goes something like this: The world is kind of melting around us. We went from the best of times to the worst of times, and we’re trying to work our way through it all.

Why talk about reacceleration?

So, why chat about it? Well, it was actually the best of times for quite a while. I don’t know if you were paying attention last year, but we saw venture capital investment nearly double; we saw more unicorns by 70% than we’ve ever seen before. We were doing more rounds; we were minting more unicorns; we were doing rounds at much higher check sizes. Every single vector was off the charts. The tech was blowing up.

“We believed that we were in charge of some amazing outcomes and that we were geniuses”

What does it mean when tech’s blowing up? Well, for a long time last year, I think we basically all thought we were geniuses. You started a business, and all of a sudden, you were raising millions or hundreds of millions of dollars like that, and everything was going great. In practice, a lot of us were like one of my favorite memes, the subway guy. The subway guy is a guy who hangs out on subway platforms. And he basically believes he’s pushing those trains forward.

In reality, he has nothing to do with the trains. And I think for a lot of us with our businesses last year, we believed that we were in charge of some amazing outcomes and that we were geniuses. And now, here we are today, and it’s the worst of times. The markets could not be worse. Every single bit of gain we’ve had in the last 18 months has been handed all the way back. And that’s put us in a not great position.

Now, if you happen to have done a deal with venture capital along the way, and you have VCs on your board or anyone who’s going to help you, fear not – if there’s one thing you can count on venture capitalists to do when times are hard is start blogging. So, they’ve been blogging for quite a while to tell us things like, “Don’t do dumb shit, do smart stuff, don’t waste money,” all this top-tier advice, the sort of value-add you really hope for. And I think that’s great and all that, but in practice, what founders need to be worried about, what founders should be worried about, are these core metrics such as burn, LTV:CAC, churn, GRR, NRR, and so on.

Now, this is not a thing that you should be worried about in economically bad times – it’s a thing you should be worried about because you started a goddamn business. You worry about burn, LTV/CAC, churn, you name it. If you’re in business or running a SaaS company, you already know them, I’m sure. The reality is healthy growth fixes all of these problems. Now, if you’re out there and you’re trying to plan, “Well, what will our next year look like?” That’s what I’m here to talk about. How do we find the parts of our business that are strong and invest in them?

First things first: Work out what’s working

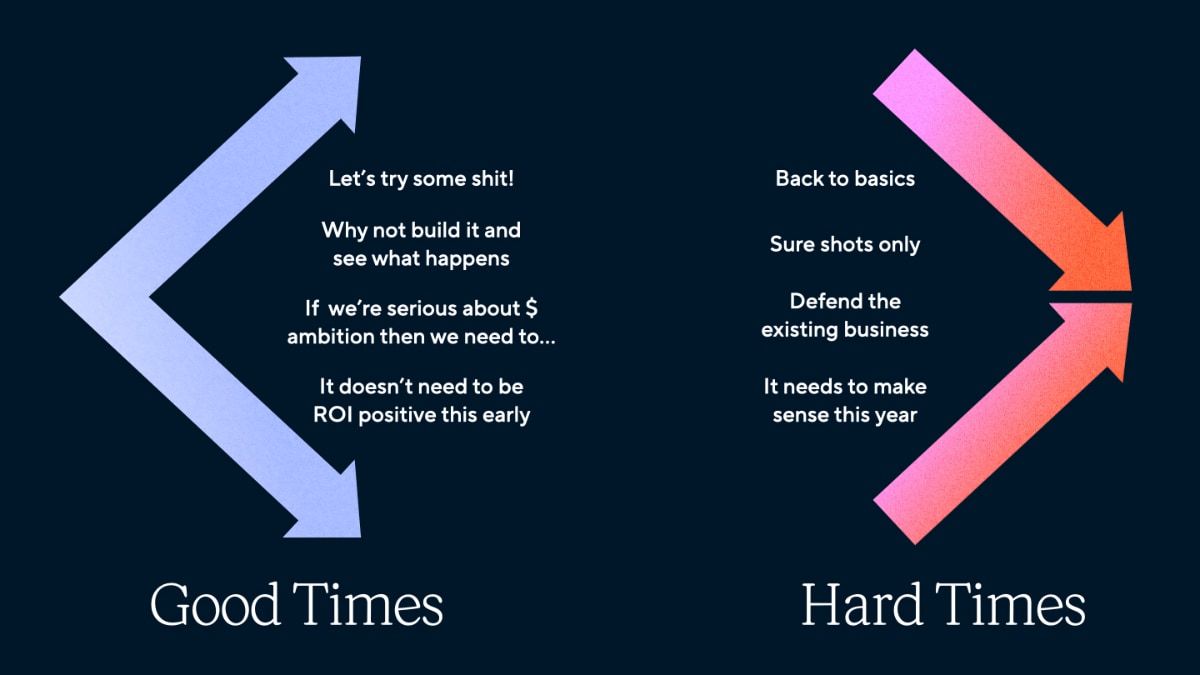

Your first job in doing this is to work out what is actually working. What is the strong part of your business? What’s working well? The reason you have to do this is that we all get a bit experimental during good times. We try shit that probably won’t work, and that’s fine. We build stuff and see who comes to buy it. We don’t necessarily think about the LTV/CAC, the CAC payback, or any of those measures. We just, generally speaking, widen the aperture and say, “Let’s try some stuff.”

And then, during bad times, we have to go and do the opposite. It is much more back to basics. What’s actually going to work? Where are the sure shots? How do we defend the existing business before we try and do anything else? And a sense of timing matters. If we’re going to spend $5 million on a new product line, it has to pay back before our bank balance runs out. That’s the sort of transition that so many companies are going through.

So, how can you do that transition? Let’s say you were doing fine in 2019, and then, out of nowhere, you had some epic year and thought, “Well, this is going to last forever.” So, you projected and planned for epic growth, but what looked like explosive growth has turned into fairly linear or super linear growth. As a result, you’re probably thinking, “What went wrong?”

Well, within any business, there are healthy pieces and sick pieces, basically. There are pieces that we can see the future in, and there are pieces that have no future. And if you look at different lines of revenue, you’ll see that some stuff, some territories, some sales, some types of customers, some parts of your technology, some product lines are growing, and some aren’t.

Now, the problem when you add something that’s not growing to a healthy business is that it hurts the business. If you add shit to a good business, you get a shit business. This is the asymmetry of mediocrity. If you have a healthy, fast-growing business, $10 million in revenue, and I give you a bag of 10 million of more revenue that’s not growing and can only shrink, your business looks a lot worse straight away. You’re now a slow-growing business. All of your growth is gone. You have to maintain and defend this bag of revenue that isn’t working. That’s the shit you don’t want to add to your business.

“Your best customers are the ones that you can sustainably acquire, that use your product deeply, not thinly, and that get differentiated value, stuff they can’t get anywhere else”

What that looks like here is you have healthy revenue, and then, when you get super ambitious, you add a lot more lines of revenue, but some of it is churny, some of it is really expensive to fund, some of it barely gets used, some of it you’re losing money on. You now look at a bigger business and that feels great, but a lot of that business isn’t actually that healthy, and that’s what you want to be careful of.

So, the challenge is to find the slices of your business that perform. And this means looking vertical by vertical, with big customers or small customers: where do they come from? What product lines do they use? Do they sign up through your sales team or online? What features do they use? Which team in the company signs up? You have to slice and dice your business to find the healthy parts. And asking all these questions will help you see, “Where are the parts of our business that we can reliably and sustainably invest in?”

Your best customers are the ones that you can sustainably acquire, that use your product deeply, not thinly, and that get differentiated value, stuff they can’t get anywhere else. If one of these three things is not true, you struggle. If you can’t get them, it’s hard to grow. If they don’t use your product a lot, it’s hard to grow. If they’re getting the same value they get anywhere else, you’re going to turn into a commodity product. And that’s the challenge you have here.

Complexity hurts your business

Now, why does this break? Well, the single biggest thing people do to hurt their business is add complexity. They make things more complicated, more multi-step processes, complex ads, landing pages, pitches, sign-up flows, routing, complex UI, complex roadmap, complex everything. It slows you down, damages the experience for your customers, and it ultimately damages the growth of your business, but you don’t notice it happening.

(And by the way, you will have people in your company who love complexity. They bathe in it at night; they want you to be as messy as possible because they’re the king of the process management and all that stuff. You have to be really careful about letting those people run your business.)

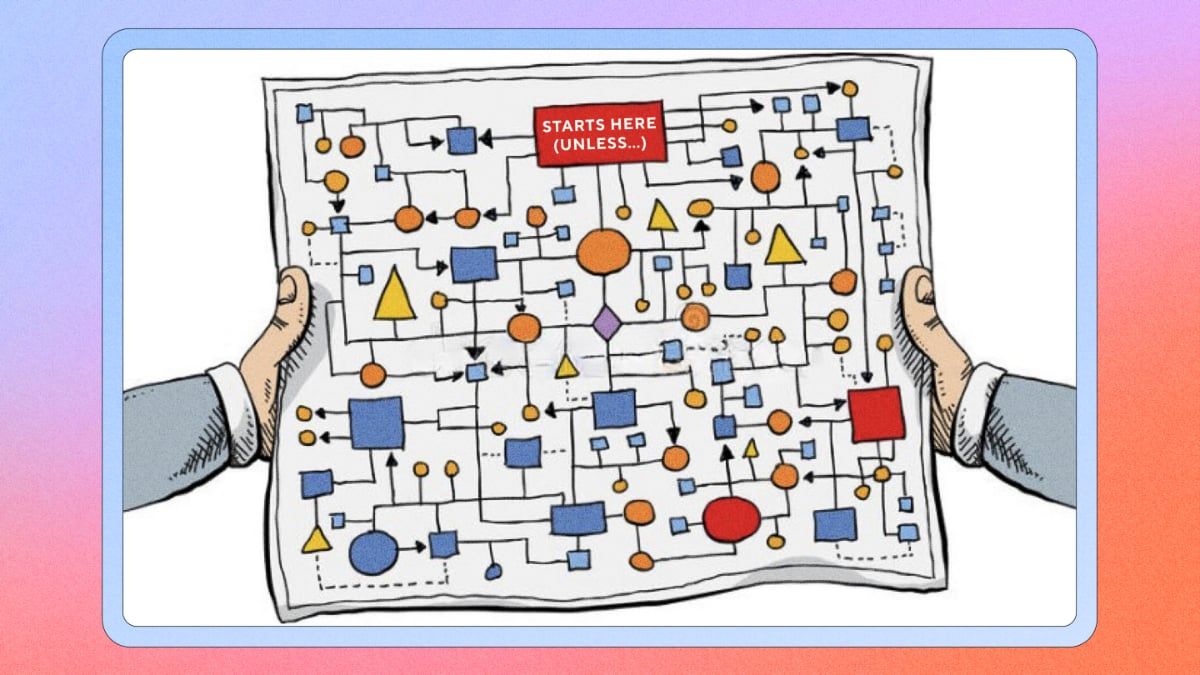

So, where does this come from? Well, you might have a pretty simple thing like homepage > sign-up, sales call > discovery, or something like that. A very simple process. And somebody will point out, “Hey, I think some people who come to our homepage might want to do something else.” And you say, “Oh, that’s interesting.” And it feels like there could be more revenue. So, you’re faced with this decision of, “Should we add more revenue or not?” And of course you’re going to choose to add more revenue, right?

And what actually happens there? Well, in those discussions, the people who are saying “let’s add the complexity” will bring spreadsheets and charts and projections and forecasts and all that sort of shit that tells you, “Don’t worry, this is going to work.” And on the flip side, the only thing you really have to combat that is, “This feels like it might not be a good idea.” And intuition will always lose to spreadsheets unless you really fight for it.

So, you go and say, “Okay, let’s do it. We’ll have two different ways of signing up,” or two different products or use cases or pricing plans or whatever. And then you repeat it, and you repeat it, and you repeat it. And before you know it, you’ve added a shitload of complexity to your business. And what you get for that is, effectively, “How do I sign up for your product, Des?” “Here you go, here’s the sign-up diagram.” And it’s an absolute nightmare.

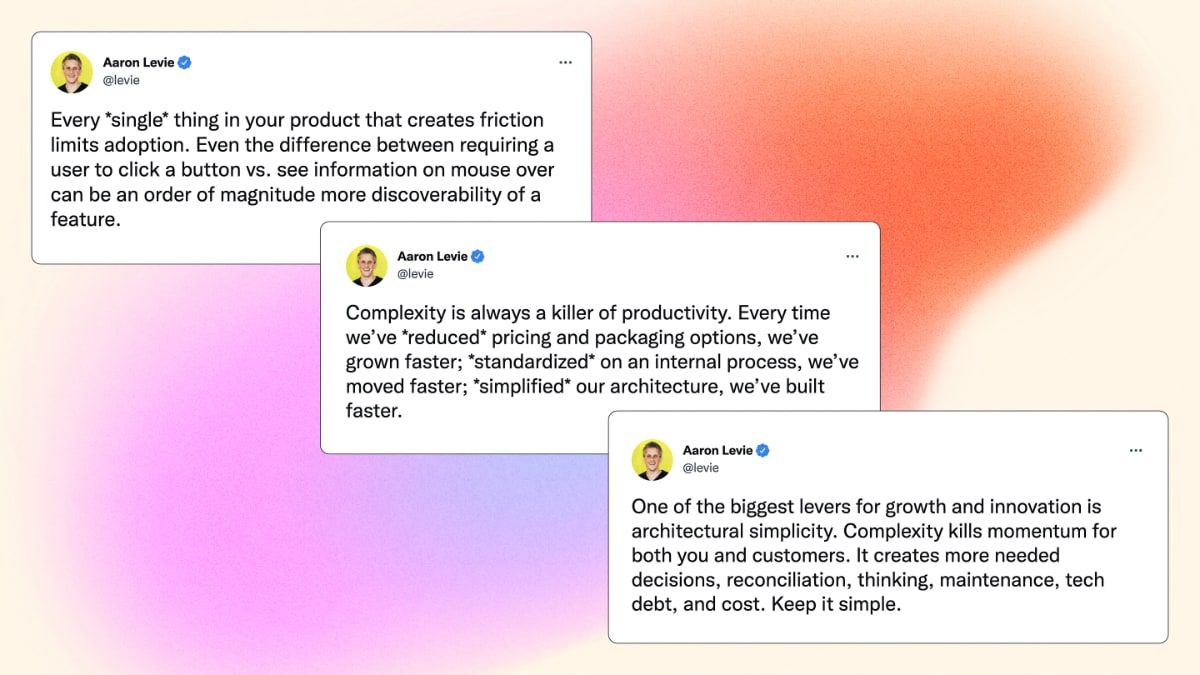

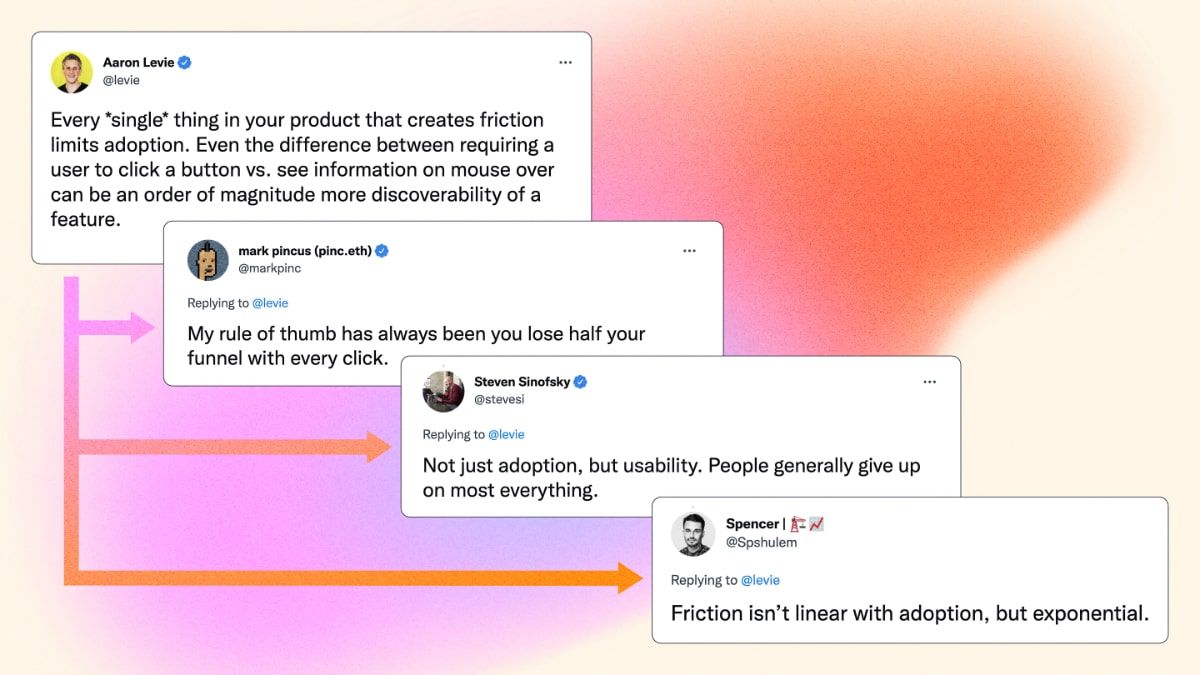

Any one of these steps in isolation looks profitable. Collectively, they are a nightmare. Aaron Levie, the CEO of Box, had some really good quotes on this. He says that “every single time they added any friction anywhere, any complexity anywhere, everything falls apart slowly.” If it happened quickly, it’d be easy, but it happens slowly.

And one of my favorite points here has been the replies in this conversation, where Mark Pincus from Zynga said, “Every step you add, you lose half your funnel.” That’s not totally correct, but if you think about it that way, you’ll get a lot better discipline.

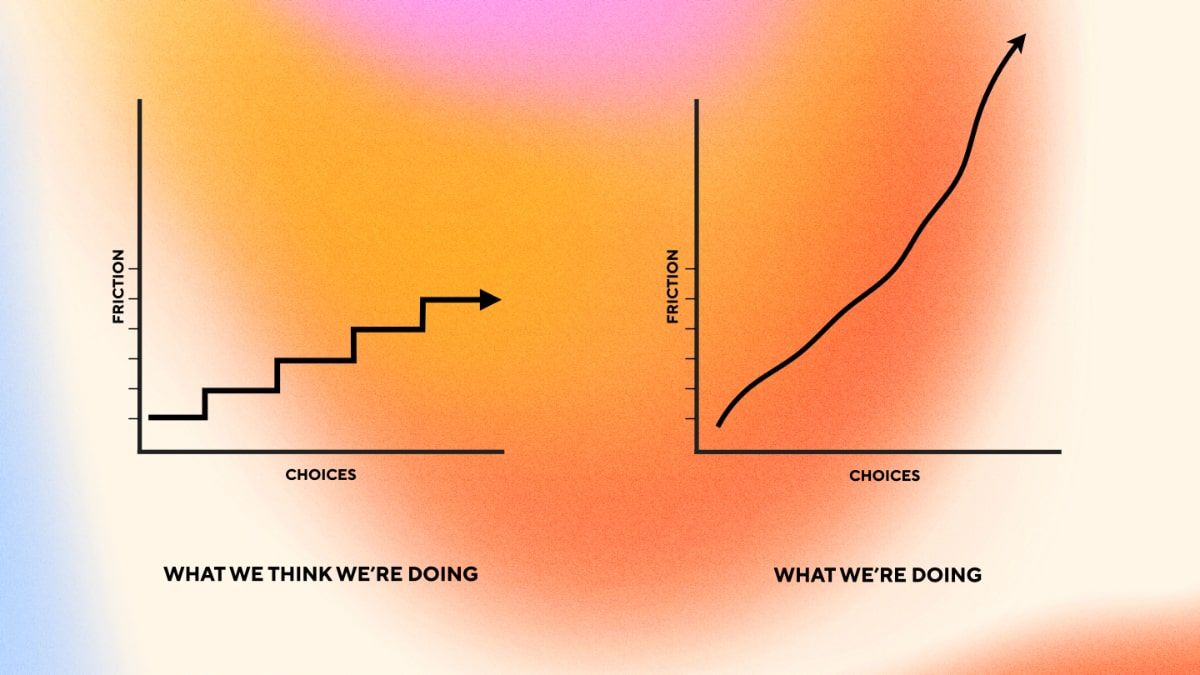

The last point is that friction isn’t linear – it’s exponential. We think we’re adding little bits of pain and getting profit, but we’re actually destroying the entire thing that made our business strong. That’s what we’re doing. It just doesn’t seem like that. So, the next time you’re asking yourself, “Should we add more customers or not?” Bear in mind you should say, “Should we add more customers by damaging UX, adding more choices, making our business more complex, or should we just improve what’s already working and simplify what’s already good?” That’s the choice you need to be making.

You have to remove the complexity from your business everywhere you can and then focus on what’s working. Going back to this idea of our bullseye customer – how do we make this business perfect for them? For instance, a made-up example from a made-up product could look like this:

- Our best customers are B2B SaaS teams of fewer than 500 people.

- They hear about us through the PM community.

- They buy us to formalize their roadmapping process.

- They typically sign up through self-serve first, and convert to sales-led later.

- They use the majority of our features except reports and our integrations, most creation/consumption in Gantt chart tool.

- Typically we see PMs and product leaders as the main users.

- Our NRR correlates perfectly with their PM headcount growth.

- Churn is driven by adoption of a bigger product with overlapping functionality (e.g. Asana, Linear).

- We compete in new business with Roadmap.io, and we lose (35% of the time) due to lack of integrations (Github, Basecamp), and also due to price (we’re ~20% more expensive).

You refine all this down. Specificity is the key to growth here. In specificity, you can design really good systems that work really well for these people.

Which leads you to some important questions. From there, you ask yourself, “What are the most important things for every function in our business to maximize the throughput for that customer type?” And you make sure you’re doing all of them in the order of impact, you make sure you’re doing nothing that isn’t that, and you definitely don’t post-rationalize things.

DO

- Ensure every function blank sheets their roadmaps and only takes inputs from target customers.

- Adapt your entire customer funnel (sales, services, support, etc.) to ensure a world-class experience for them.

- Ensure all your metrics/dashboards track the success of this type of customer.

- Kill all activities that don’t support the strategy, even and especially the “harmless” ones.

DON’T

- Post-rationalise your roadmaps, e.g. “let’s finish off this project because it’ll probably help them too”.

- Let numerous exceptions and edge cases keep the old initiatives alive.

- Celebrate successes that have nothing to do with your new refined plan.

- Continue decisions/meetings/org charts that were predicated on the old plan.

The worst thing you can do here is post-rationalization. What that looks like is you tell your team, “We’re going to try and nail this customer type.” And they say, “Got it.” And then they look at the roadmap and go, “Well, I could see how that could help.” So, they keep it on the roadmap. That is not the right thing to do. The question is, “What is the most important thing, with the resources you have, to drive this strategy forward?” That’s the only question you can ask.

To put it another way, we’re saying to invest in the engines of growth of your business, do not invest in mediocrity. There will be revenue pain from doing this as the parts of your business that were never working continue to not work. The only difference in this approach is you’re deliberately building for a new world as opposed to spending the best years of your life trying to stave off death for the sake of a few extra years of survival. That is not the way to run a startup. Remember, runways are not roads – they don’t take you to your destination. A runway in startup land is for you to take off. That’s what they’re there for.

Second things second: Grow your business

The next thing is growing your business. If you have refined your business down to a current and healthy business, where do you go from here? There are, generally speaking, four directions you can go, and I’ll walk you through each of them.

- Sell to larger companies (aka go upmarket): If you’re currently selling to small customers, you can sell to bigger customers. They will generally spend more money.

- Sell more stuff to current buyers within your customer base: You can work out what else your current customers would buy off you. This effectively increases your “share of wallet”. For example, if you sell expense tracking, maybe the same buyer also needs a perks & benefits product or a travel planning product.

- Sell more stuff to new buyers within your customer base: You can think about who the adjacent buyers are within your company, so if you’re selling to marketing, could you also sell to sales, if you’re selling to engineering could you also sell to product.

- Package your product for specific new verticals: You can take everything you currently have but “tailor” it for new verticals. If you were time tracking, you could be time tracking for support teams or something like that. You can get really specific for verticals.

But I have to warn you. Every single one of these approaches runs the risk of doing the exact damage I talked about minutes ago. They are hard, they are expensive, and they will necessarily involve adding complexity. Your job as founders is to make sure that the complexity is really profitable, not just another unhealthy lump of revenue. So, to put it another way, don’t do this until you actually have a healthy base. Otherwise, you’re just piling shit on top of more shit, and it won’t work out.

Sell to larger companies

If you want to take your current product upmarket, what’s good about that? You’ll get more revenue, lower churn, stickier usage, and longer contracts. But what’s hard is you have to build a lot more stuff. There’ll be endless requests. You have to do a lot of investment in your platform – security, permissions, and all that stuff bubbles up. All of a sudden, with marketing, you’d have to talk to Forrester and Gartner, sales will see longer cycles, and your support team will be under a higher demand.

Sell more stuff to current buyers within your customer base

If you want to build more products for your current customers, that’s, again, more annual contract value. It increases the posture of your product, it’s harder to quit when they use you for everything, and you’ll have an existing trusting buyer already. The hard part is it’s basically a brand-new startup. You have to go and find a whole new innovation challenge to solve.

“You need to make sure there’s an umbrella for your brand that makes it all make sense”

You need to make sure your brand makes sense. You can’t be like one of these, “We’re time tracking plus roadmap planning.” It doesn’t make sense. You need to make sure there’s an umbrella for your brand that makes it all make sense. From a sales perspective, there’s an opportunity or a challenge. You need to get good at cross-selling and upselling. And how do we actually move around this sort of business? And then, generally speaking, the more product you add, the harder it gets.

Sell more stuff to new buyers within your customer base

If you want to sell to new buyers within your current customer base, it has most of the advantages. One big one here is you can then go wall-to-wall. This is the dream for most SaaS companies. They like to be installed in every department. Think of Workday or Slack – they basically have users in every corner of the business. The hard part here is it’s a brand-new buyer. You probably don’t know anything about them. You probably don’t know how to cater to them.

From a marketing perspective, it’s an even higher-level thing if you need to sell and relate to the sales team, marketing teams, and support teams. From a sales perspective, it’s a harder cross-sell, because you’re asking Joey, the head of procurement, to introduce you to Johnny, the head of road mapping. That’s just trickier. And lastly, you end up supporting multiple customer types.

Package your product for specific new verticals

And the last method you have is packaging your product for new verticals. What’s good here is you will oftentimes be able to attract new lines of revenue for not a lot of new products, and you’ll also see less competition the more specific the vertical gets. The hard part is that platform work is necessary to allow you to really tailor the product so you’re speaking the language of your customers. If you’re doing project management and you’re trying to sell to sports teams, it might not be a new project – it might be a new training drill, and they need to be able to customize the product to really fit their use case. Your current channels for marketing probably won’t work. And from a sales perspective, it’s a whole new domain. You need to understand a different type of buyer.

Steps to reaccelerate your business

So, as you weigh up these opportunities, there are four things that say when you’re really fighting to grow. One is to remember friction is exponential, not linear.

Two is that being everything for somebody, generally speaking, is better than being something for everybody. Something for everyone has an advantage in that you can get a foot in the door, and you’ll always be able to find something to sell, but being everything changes the game because they’ll never quit you if you actually solve all their problems.

“Find the strongest parts of your core business, strip the complexity, focus your roadmap on optimizing for that strong core, and only then should you explore your four revenue engines”

The third piece is, generally speaking, you want as much cash as possible from as little code as possible. You don’t want a massive product if you can avoid it. It’s expensive to build, maintain, support. The only caveat I’d say to that is you need to be complex enough so that you’re not easy to copy.

And then, lastly, be aware of the asymmetry of mediocrity. A lot of you, when you’re tempted to grow your business, will be tempted to add things that aren’t great to it. If I add a cockroach to a bowl of strawberries, that’s disgusting, right? You’re not going to eat any of those strawberries. Now, if I add a strawberry to a bowl of cockroaches, you’re still not touching the fucking bowl. And that’s the asymmetry piece. When you add bad things to a business, there’s no easy way to undo that. And that is a pain that you’ll spend a long time trying to carve out.

My firm message is:

- Find the strongest parts of your core business.

- Strip away the complexity.

- Focus your roadmap on optimizing for that strong core.

- And only then should you explore your four revenue engines.

I’m Des Traynor from Intercom. I hope this was useful. Thank you very much.